eBPF Verifier: Why the Kernel Can Safely Run eBPF Programs

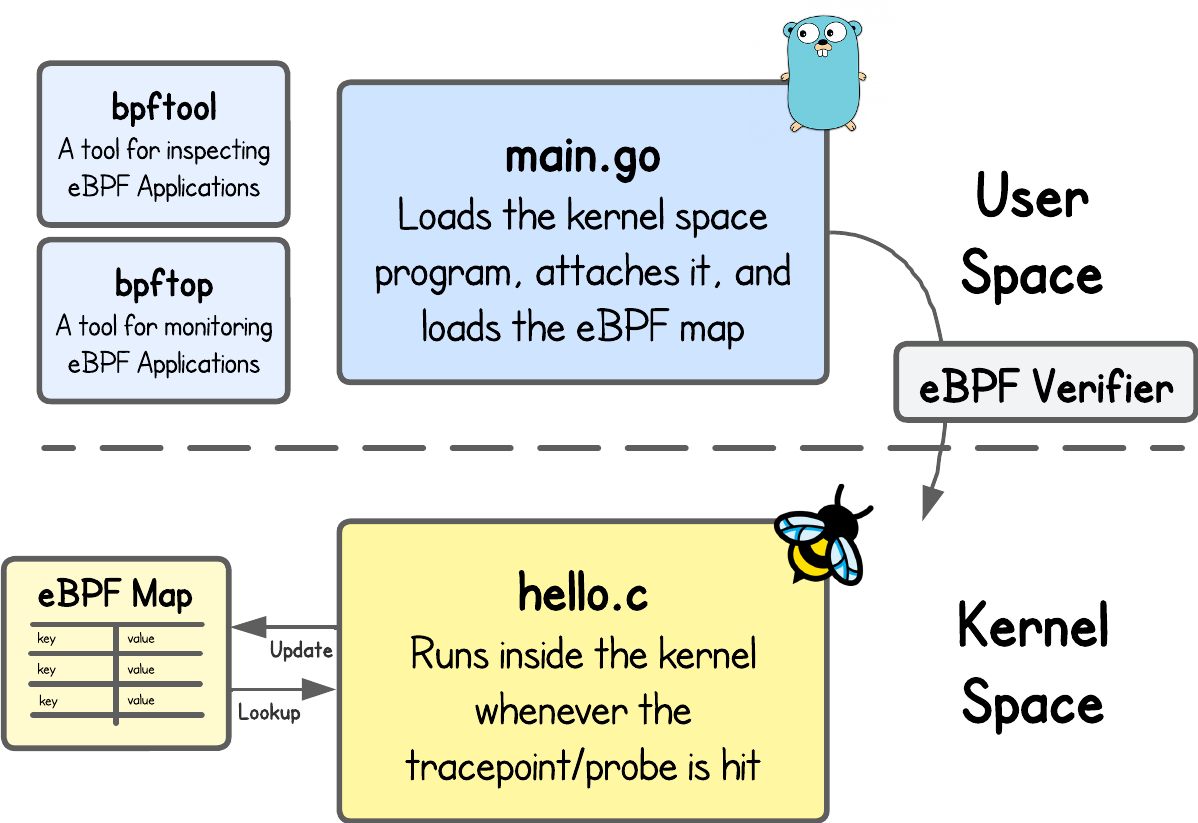

When you start the tutorial, you’ll see a Term 1 terminal and an IDE on the right-hand side. You are logged in as laborant, and the current working directory already contains the ebpf-hello-world folder. Inside, you’ll find the eBPF Hello World labs, implemented with ebpf-go — a Golang eBPF framework developed as part of the Cilium project.

This tutorial serves as the continuation of From Zero to Your First eBPF Program, Storing Data in eBPF: Your First eBPF Map and Inspecting and Monitoring eBPF Applications, expanding on the introduced concepts.

In this part, you’ll learn how the eBPF verifier ensures that eBPF code can run safely in the kernel.

The code for this lab is located in the ebpf-hello-world/lab4 directory. The program is intentionally broken—meaning the verifier will reject it if you try to run it. Your task in the upcoming steps is to understand why it fails and then work on fixing it.

eBPF Verifier

We’ve mentioned verification several times throughout these tutorials, so you already know that when you load an eBPF program into the kernel, this process ensures that the program is safe.

This verification is done by the eBPF verifier. And by “safe”, we don’t mean cybersecurity-related security, but simply that the program won’t crash the system or cause a kernel panic.

💡 Safe execution is one of the biggest advantages of eBPF programs compared to traditional kernel modules.

To achieve this, the verifier checks every possible execution path through your program and validates that each instruction is safe. This includes:

- Validating Helper Functions: Ensures only approved kernel helper functions are called, as different helper functions are valid for different BPF program types. (Remember the

sudo bpftool feature probeoutput?) - Validating Helper Function Arguments: Ensures the arguments passed to helper functions are valid.

- Checking the License: Ensures that if you are using an eBPF helper function that’s licensed under GPL, your program also has a GPL-compatible license.

- Checking Memory Access: Ensures the program only reads and writes to memory it is allowed to access.

- Checking Pointers Before Dereferencing Them: Ensures pointers in code are safe and not null or out of bounds before use.

- Accessing Context: Ensures that the program accesses only the fields in the input context structure it is allowed to.

- Running to Completion: Ensures the program will eventually finish instead of running forever.

- Loops: Ensures that loops are bounded and cannot cause infinite execution.

- Checking the Return Code: Ensures the program returns a valid value for its type of hook.

- Invalid Instructions: Rejects any instruction that is not supported or not allowed in eBPF.

- Unreachable Instructions: Flags and removes instructions that the program can never reach during execution.

In the next sections, we’ll look at a few of these checks with practical examples and tips for debugging them. For more details about the eBPF verifier itself, we recommend Learning eBPF, Chapter 6: The eBPF Verifier book.

Checking the License

When an eBPF program is loaded into the kernel, the verifier inspects which helper functions it uses. If any of those helpers are marked “GPL-only,” the program must declare a GPL-compatible license.

But how can one check if the helper function in use is GPL-licensed?

It’s not the most convenient approach, but you can determine this for each helper function by checking the Linux kernel source for the corresponding <helper-function>_proto struct definition.

For example, the prototype for bpf_probe_read_user_str() is bpf_probe_read_user_str_proto, where the .gpl_only boolean field indicates that the helper is restricted to GPL-licensed programs.

Does that mean one also has to license the user-space part of the eBPF application as GPL?

Not really. When it comes to user space, your eBPF loader code and supporting libraries do NOT need to be GPL-licensed, only the in-kernel eBPF program does.

This separation allows companies and projects to keep user space tooling under permissive licenses while still running GPL-licensed code in the kernel. For more details, see the eBPF Licensing Guide.

To demonstrate this, open the ebpf-hello-world/lab4/hello.c file. You’ll find calls to helpers such as bpf_probe_read_user_str(), bpf_map_update_elem() and bpf_map_lookup_elem() - but notice there’s no license definition anywhere in the code:

SEC("tracepoint/syscalls/sys_enter_execve")

int handle_execve_tp(struct trace_event_raw_sys_enter *ctx) {

const char *filename = (const char *)ctx->args[0];

struct path_key key = {};

long n = bpf_probe_read_user_str(key.path, sizeof(key.path), filename);

if (n <= 0) {

return 0; // couldn't read the path

}

__u64 *val = bpf_map_lookup_elem(&exec_count, &key);

if (val) {

*val += 1;

} else {

__u64 init = 1;

bpf_map_update_elem(&exec_count, &key, &init, BPF_NOEXIST);

}

...

If you build and run this program, you’ll see the following verifier error:

cannot call GPL-restricted function from non-GPL compatible program

This is expected: like mentioned above or if you check the Linux kernel source, you’ll notice that among these helpers, bpf_probe_read_user_str() is GPL-only.

To resolve this, you need to declare your program’s license explicitly. Add the following line anywhere in your code — top, bottom, or even in the middle doesn’t matter, as long as it’s present:

char _license[] SEC("license") = "GPL";

Does it always have to be GPL? What about dual-licensed options like Dual MIT/GPL?

Not necessarily. The eBPF license string just needs to be GPL-compatible. The Linux kernel accepts several options, including GPL, GPL v2, Dual BSD/GPL, Dual MIT/GPL, and Dual MPL/GPL.

Many projects actually choose a dual license in order to:

- satisfy the eBPF verifier in case of GPL-ed helper functions

- give other projects flexibility to integrate/reuse parts of the eBPF code without being forced to adopt GPL for their entire codebase

For full details on accepted annotations, see the kernel’s license-rules documentation.

Re-run the program and see it works as expected.

Checking Pointers Before Dereferencing Them

Let’s say you want to validate or debug your program by printing which binary paths are executed and stored in the eBPF map.

To do this, you might try adding the following lines just before the end of your eBPF program:

...

__u64 *val = bpf_map_lookup_elem(&exec_count, &key);

if (val) {

*val += 1;

} else {

__u64 init = 1;

bpf_map_update_elem(&exec_count, &key, &init, BPF_NOEXIST);

}

// Step 2: Print `key.path` and `*val`

bpf_printk("execve: %s (count: %llu)\n", key.path, *val);

return 0;

}

However, this won’t really work. If you try to run the program, you’ll hit a verifier error such as:

last insn is not an exit or jmp (2 line(s) omitted)

At first glance, this error is a bit misleading. Technically, it’s the verifier’s way of saying “your function doesn’t always end with a return instruction.”

But since we clearly have a return 0; in place, it feels like the verifier is just trolling us 😅.

And it’s also pretty clear the error only showed up after we added the new line. That means something about it must be wrong.

We could now disassemble the hello_bpf.o kernel object (built with go generate command) to track down the error, but that would be another tutorial on its own. In this case, the issue is actually visible directly in our code.

The problem is that we never verify whether *val points to valid memory. The bpf_map_lookup_elem helper may in fact return null which is not a valid memory location and cannot be safely dereferenced. To fix this, we need to move our bpf_printk() statement inside the if (val) branch:

...

__u64 *val = bpf_map_lookup_elem(&exec_count, &key);

if (val) {

*val += 1;

} else {

__u64 init = 1;

bpf_map_update_elem(&exec_count, &key, &init, BPF_NOEXIST);

}

// Step 2: Print `key.path` and `*val`

if (val) {

bpf_printk("execve: %s (count: %llu)\n", key.path, *val);

}

return 0;

}

To summarize this, always check pointers before dereferencing them.

Running to Completion and Complexity Limit

Another important verifier check is to make sure the program runs to completion in a relatively short amount of time. Otherwise, there is a risk that it might consume resources indefinitely, possibly containing infinite loops that could hang the kernel completely.

Just imagine our eBPF program attached to the execve() syscall running for too long. It could cause massive delays in the termination of the execve syscall and consequently have a significant impact on the system.

So, when eBPF was introduced, there were two parameters that limited its size:

- The maximum number of eBPF bytecode instructions for a program: 4096

- The complexity limit: 32768

You may think of the second number as the total number of instructions accumulated over all execution paths. So if a program had many logical branches or loops and required too much effort from the verifier, it would fail to load, even if it had fewer than 4096 instructions.

To allow for more complex eBPF programs, both limits were raised in a commit in Linux 5.2 to 1 million instructions.

If your program is too complex and classified as hogging the system for too long, you'll end up seeing the following error:

BPF program is too large. Processed 1000001 insn

But in reality, eBPF programs tend to be small, and the one-million-state complexity limit is big enough that most use cases will never hit it. Only some advanced projects like Cilium may be facing it, and they need to regularly adjust their code to satisfy the verifier's requirements.

In our personal experience, the easiest and most trivial way to debug verifier code is by using a combination of bpf_printk() function and commenting/uncommenting lines of code to determine the cause of the verification error and take it from there either through the byte code or general understanding of the checks that we discussed above.

When still learning eBPF, getting code through the verifier seemed like a dark art and you might find yourself needing assistance to resolve verifier errors. And that's okay - we've all been there. The eBPF community Slack channel is a good place to ask for help or just ping us directly.

💡 There's also a eBPF verifier errors GitHub repository that collects different verifier errors and their resolution. Although it's a gamble, whether it will be maintained over time but a nice resource when you're encountering issues.

💡 One thing to bear in mind is that the verifier works on eBPF bytecode, not directly on the source. And that bytecode depends on the output from the compiler. Because of things like compiler optimization, a change in the source code might not always result in exactly what you expect in the bytecode, so correspondingly it might not give you the result you expect in the verifier’s verdict.

For example, the verifier will reject unreachable instructions, but the compiler might optimize them away before the verifier sees them.

Congrats, you've came to the end of this tutorial. 🥳

The last four labs covered the fundamentals of eBPF — now it’s time to put your knowledge to the test. Head over to the Challenge and see how much you’ve learned!