Storing Data in eBPF: Your First eBPF Map

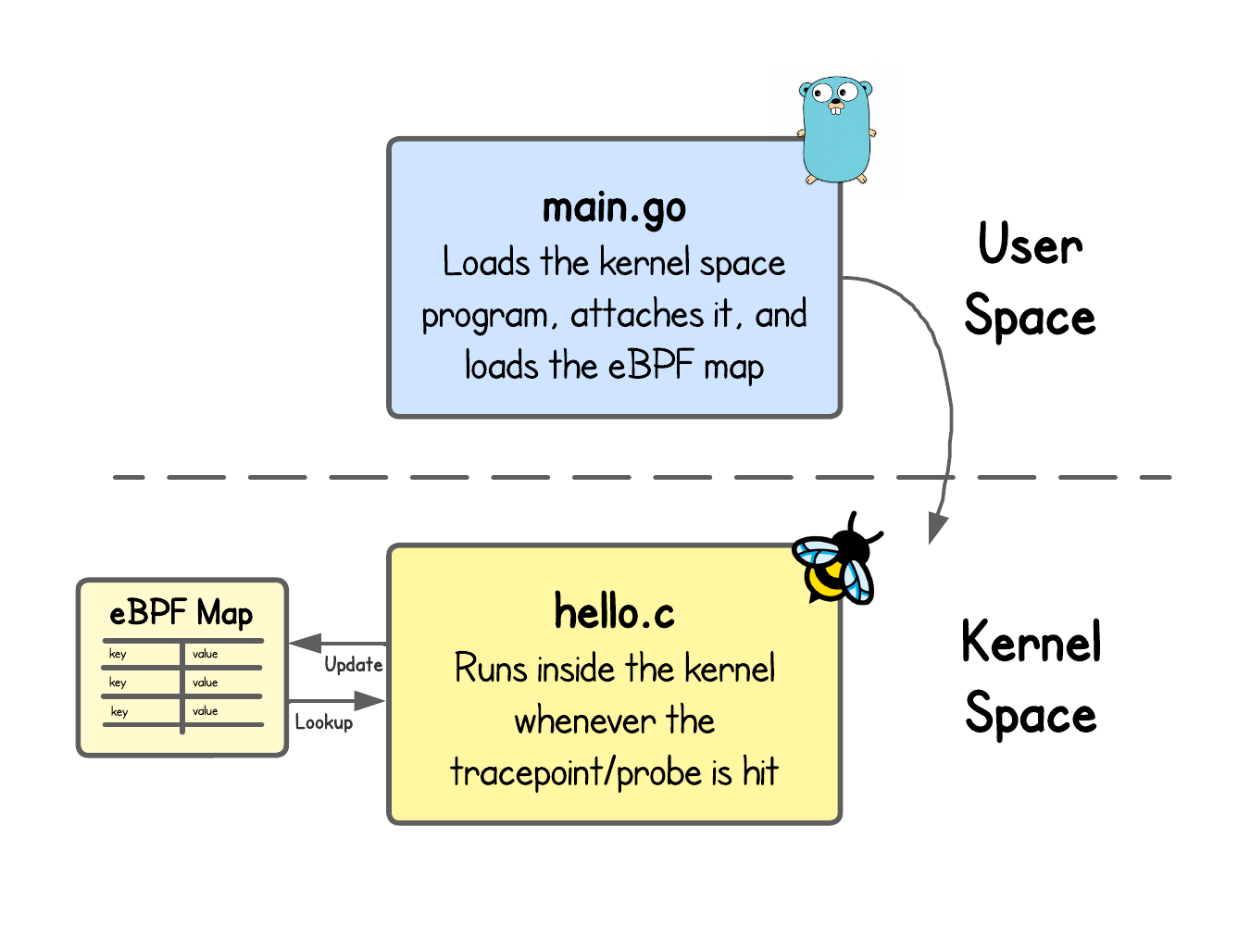

When you start the tutorial, you’ll see a Term 1 terminal and an IDE on the right-hand side. You are logged in as laborant, and the current working directory already contains the ebpf-hello-world folder. Inside, you’ll find the eBPF Hello World labs, implemented with ebpf-go — a Golang eBPF framework developed as part of the Cilium project.

This tutorial serves as the continuation of From Zero to Your First eBPF Program, expanding on the introduced concepts.

In this part, you’ll learn about eBPF Maps, which allow data to be persisted or shared between eBPF programs and user space services. To keep things straightforward, we’ll skip sending events to user space for now. Instead, we’ll focus on how to persist a state inside an eBPF program. Through a simple example, you’ll learn to use an eBPF map to store a counter that tracks how many times specific binary executables are triggered.

Storing State in eBPF Maps

When you want to store a state in eBPF kernel program, there are several eBPF Map types you can choose from. Just to name a few:

- Hash Map: A generic key/value store where both keys and values can be of arbitrary types

- Array Map: Similar to hash map, but key is always 32-bit unsigned integer

- Per-CPU Hash/Array Map: Same as hash (and array) map, but each CPU gets its own copy of it

- LRU Hash Map: A hash map with Least Recently Used eviction policy, automatically removing old entries after being full

- Ring Buffer: Used for passing kernel events data from kernel space to user space

Which map type to use depends heavily on your specific use case. We’ll cover the design choices in another tutorial, but for our example, we’ll just use a Hash Map.

Before we can use an eBPF map in our kernel program, we need to define it. Navigate to the ebpf-hello-world/lab2 folder with either using the Term 1 terminal or the IDE. Then, open the hello.c file.

Inside, add the following code lines and eBPF map definition (under Step 1):

#define MAX_PATH 256

struct path_key {

char path[MAX_PATH];

};

struct {

__uint(type, BPF_MAP_TYPE_HASH);

__uint(max_entries, 16384);

__type(key, struct path_key);

__type(value, __u64);

} exec_count SEC(".maps");

As you can see in the code, our eBPF map stores key/value pairs, where:

- The key is a

struct path_key, which contains the binary execution path (e.g.,/usr/bin/ls,/usr/bin/cat) - The value is a

__u64integer that counts how many times that binary has been executed (e.g.,1,2,3, ...)

What about `max_entries` parameter?

The max_entries field defines the upper bound on how many key/value pairs a map can hold.

In this example, we set it to 16384 but in practice, the value can range from just a few (e.g., 1, 128, 1024) up to hundreds of thousands or even millions, depending on kernel configuration (ulimit, locked memory) and available RAM.

To avoid hitting the memory lock limit (RLIMIT_MEMLOCK), we include the following code in the user space program:

...

func main() {

// By default (for Linux < 5.11), Linux sets a RLIMIT_MEMLOCK (memory lock limit) that restricts how much memory a process can lock into RAM.

// eBPF maps and programs use pinned memory that counts against this limit.

// If you don’t raise or remove the limit, loading larger eBPF programs or maps will fail with errors like “operation not permitted” or “memory locked limit exceeded.”

if err := rlimit.RemoveMemlock(); err != nil {

log.Fatal("Removing memlock:", err)

}

...

NOTE: Starting with Linux v5.11, the memory accounting and limiting was moved from rlimit to cGroups. In other words, if the resource limits need to be raised, it should be done so with the memory.max setting on the cGroup.

Technically, this eBPF map could now be updated (store/read/delete key/value pairs) from any eBPF kernel or user space program, but in our case we just update it from our eBPF kernel function. And we do so by modifying our kernel program as such (under Step 2):

SEC("tracepoint/syscalls/sys_enter_execve")

int handle_execve_tp(struct trace_event_raw_sys_enter *ctx) {

// The eBPF program reads the first argument of the input context `struct trace_event_raw_sys_enter`, whose

// values/parameters align with the execve() system call: https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man2/execve.2.html

// You can also view this allignment using `sudo cat /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/events/syscalls/sys_enter_execve/format`

// * The first argument `ctx->args[0]` is `const char *pathname` -> either a binary executable, or

// a script starting with a line of the form `#!interpreter [optional-arg]` (e.g. your bash scripts)

const char *filename = (const char *)ctx->args[0];

// * The second argument `ctx->args[1]` is `char *const argv[]` -> array of pointers to strings passed to the

// new program as its command-line arguments

// * The third argument `ctx->args[2]` is `char *const envp[]` -> array of pointers to strings, conventionally of

// the form key=value, which are passed as the environment of the new program (a.k.a. env variables)

// Instantiate and store the first argument as our key of the eBPF map using `bpf_probe_read_user_str` which is a

// handy eBPF helper function, to copy a NULL terminated string from an (unsafe) user address

struct path_key key = {};

long n = bpf_probe_read_user_str(key.path, sizeof(key.path), filename);

// Validate the copy operation was succesfull

// On success, the strictly positive length of the output string, including the trailing NULL character is returned.

// On error, a negative value is returned.

if (n <= 0) {

return 0;

}

// Check whether this key (binary executable path) already exists in our map and

__u64 *val = bpf_map_lookup_elem(&exec_count, &key);

if (val) {

// Update the value of the counter under that key we found in the map

// NOTE: this is not a safe way to update the value - we'll learn about atomic operations in the upcoming tutorial

*val += 1;

} else {

// If this binary is executed for the first time since our eBPF application has been run, we just set the counter value to 1

__u64 init = 1;

bpf_map_update_elem(&exec_count, &key, &init, BPF_NOEXIST);

}

// Optional: print to debug

bpf_printk("execve: %s\n", key.path);

return 0;

}

It might feel like a lot to take in at first, so we’ve added detailed comments to each line of code.

The interesting lines of code, related to the eBPF map are:

bpf_map_lookup_elem(map, key)- Looks up an element in the map by key and returns a pointer to the value in kernel space if it exists, or NULL if not found.bpf_map_update_elem(map, key, value, flags)- Inserts or updates a map entry. Theflagsparameter controls the update behavior:BPF_ANY: create new or update existingBPF_NOEXIST: create only if key doesn’t existBPF_EXIST: update only if key exists

More information about eBPF map helpers

Some other eBPF map helper functions that you’ll encounter in the wild:

bpf_map_delete_elem(map, key)for deleting the map entrybpf_map_lookup_and_delete_elem(map, key)for looking up and deleting the entry right afterbpf_map_push_elem(map, value, flags)for pushing an element into a Queue, Stack and Bloom filter eBPF Maps.bpf_map_pop_elem(map, value_out)for popping (removing) an element from a Queue and Stack eBPF Maps.bpf_map_peek_elem(map, value_out)for retrieving the top element from a Queue, Stack and Bloom filter eBPF Maps without removing it.- and others..

⚠️ Not all helpers are supported by every map type. For details, check the official eBPF documentation to see which helpers are available for each map type.

Building and Running the eBPF Application

With that behind us, we can now build and run our eBPF application, using:

cd ebpf-hello-world/lab2 # Go inside the ebpf-hello-world/lab2 folder if you haven't already

go generate

go build

sudo ./lab2

If you looked closely at the code, you’ll must have seen that our eBPF program calls bpf_printk(). This means we should get a log message each time a certain binary is executed.

To view these logs, open the Term 2 tab on the right (click the + at the top), and run:

sudo cat /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/trace_pipe

It's quite unlikely you won't see any logs. But this could be the case, since there is little going on in a small VM like ours, so let's execute some process ourself.

Open the third Term 3 tab, and execute:

cat /etc/os-release

# or

uname -a

Inspecting the eBPF Map

But we already learned how to view the logs in the first tutorial and it doesn't really tell us a lot about how many times certain binaries were executed.

A more useful approach would be to inspect the contents of our eBPF map directly. That way, we would see each key (the binary name) along with its value (the number of times it was executed).

This is achieved using bpftool.

As this is an eBPF playground, this tool is already installed. Open (or go back to Term 3 terminal) and list all the eBPF maps loaded on the system using:

sudo bpftool map list

The output will be similar to this:

303: hash name exec_count flags 0x0

key 256B value 8B max_entries 16384 memlock 5397440B

btf_id 490

305: array name .rodata flags 0x480

key 4B value 12B max_entries 1 memlock 8192B

btf_id 491 frozen

On the right side of the output, the IDs of the eBPF maps are listed. Using the ID we can print it's content using:

sudo bpftool map dump id 303 # Update the ID according to your output

Output of `bpftool map list` explained in detail

Our exec_count eBPF map that we loaded using our application includes the following parameters:

303→ the map ID assigned by the kernel, which can be used to reference the map (e.g., withbpftool map dump id 303)hash→ the map type, in this case a hash map (BPF_MAP_TYPE_HASH)name exec_count→ the map’s name, set when it was defined in the eBPF program (e.g.,SEC("maps") struct { ... } exec_count)flags 0x0→ creation flags for the map, with0x0meaning no special flags were used. Check the available flags for each map type under the flags section in the documentationkey 256B→ the key size, where each key is 256 bytes long corresponding to our#define MAX_PATH 256preprocessor macro definition macrovalue 8B→ the value size, where each value is 8 bytes corresponding to our count variable of type__u64max_entries 16384→ the maximum number of key-value pairs the map can holdmemlock 5397440B→ the amount of pinned kernel memory reserved for this map (about ~5.15 MB)btf_id 490→ the BPF Type Format (BTF) ID associated with this map. We'll learn about BTF later on

❓ What about the second .rodata eBPF map?

We’ll dig into this in more detail later, but here’s the short answer.

In eBPF, things work differently compared to normal C programs:

- There’s no heap (so you can’t just

mallocmemory). - You only have a small stack and some pointers into kernel space.

To work around this, array maps are automatically created (during eBPF program loading) as a storage for global data. In our case, the data considered global is the string passed to the bpf_printk function, as explained in the documentation.

We can confirm this using:

sudo bpftool map dump id 305 # Update the ID according to your output

[{

"value": {

".rodata": [{

"handle_execve_tp.____fmt": [101,120,101,99,118,101,58,32,37,115,10,0

]

}

]

}

}

]

Where the sequence 101,120,101,99,118,101,58,32,37,115,10,0 is ASCII for execve: %s\n. Exactly the format string we provided to our bpf_printk function call.

That's it for this tutorial - and no worries, we'll see a lot more of bpftool in the the next tutorial.

If along the you encountered any issues, look inside the ebpf-hello-world/lab3 folder for the complete solution.

Legacy eBPF Maps

Not to get confused, there is a legacy way of defining maps using the struct bpf_map_def type.

struct bpf_map_def exec_count = {

.type = BPF_MAP_TYPE_HASH,

.key_size = sizeof(struct path_key),

.value_size = sizeof(int),

.max_entries = 16384,

.map_flags = BPF_F_NO_PREALLOC,

} SEC("maps");

The major downside of this "method" is that key and value type information is lost, which is why it was replaced.

Congrats, you've came to the end of this tutorial. 🥳

In the next tutorial, you’ll learn how to inspect eBPF programs and maps loaded into the kernel with bpftool, and monitor their activity with bpftop.