How to Build Smaller Container Images: Docker Multi-Stage Builds

If you're building container images with Docker and your Dockerfiles aren't multi-stage, you're likely shipping unnecessary bloat to production. This not only increases the size of your images but also broadens their potential attack surface.

What exactly causes this bloat, and how can you avoid it?

In this article, we'll explore the most common sources of unnecessary packages in production container images. Once the problem is clear, we'll see how using Multi-Stage Builds can help produce slimmer and more secure images. Finally, we'll practice restructuring Dockerfiles for some popular software stacks - both to better internalize the new knowledge and to show that often, just a little extra effort can yield a significantly better image.

Let's get started!

Why is my image so huge?

Almost any application, regardless of its type (web service, database, CLI, etc.) or language stack (Python, Node.js, Go, etc.), has two types of dependencies: build-time and run-time.

Typically, the build-time dependencies are much more numerous and noisy (read - have more CVEs in them) than the run-time ones. Therefore, in most cases, you'll only want the production dependencies in your final images.

However, build-time dependencies end up in production containers more often than not, and one of the main reasons for that is:

⛔ Using exactly the same image to build and run the application.

Building code in containers is a common (and good) practice - it guarantees the build process uses the same set of tools when performed on a developer's machine, a CI server, or any other environment.

Running applications in containers is the de facto standard practice today. Even if you aren't using Docker, your code is likely still running in a container or a container-like VM.

However, building and running apps are two completely separate problems with different sets of requirements and constraints. So, the build and runtime images should also be completely separate! Nevertheless, the need for such a separation is often overlooked, and production images end up having linters, compilers, and other dev tools in them.

Here are a couple of examples that demonstrate how it usually happens.

How NOT to organize a Go application's Dockerfile

Starting with a more obvious one:

# DO NOT DO THIS IN YOUR DOCKERFILE

FROM golang:1.23

WORKDIR /app

COPY . .

RUN go build -o binary

CMD ["/app/binary"]

The issue with the above Dockerfile is that golang

was never intended as a base image for production applications.

However, this image is the default choice if you want to build your Go code in a container.

But once you've written a piece of Dockerfile that compiles the source code into an executable,

it can be tempting to simply add a CMD instruction to invoke this binary and call it done.

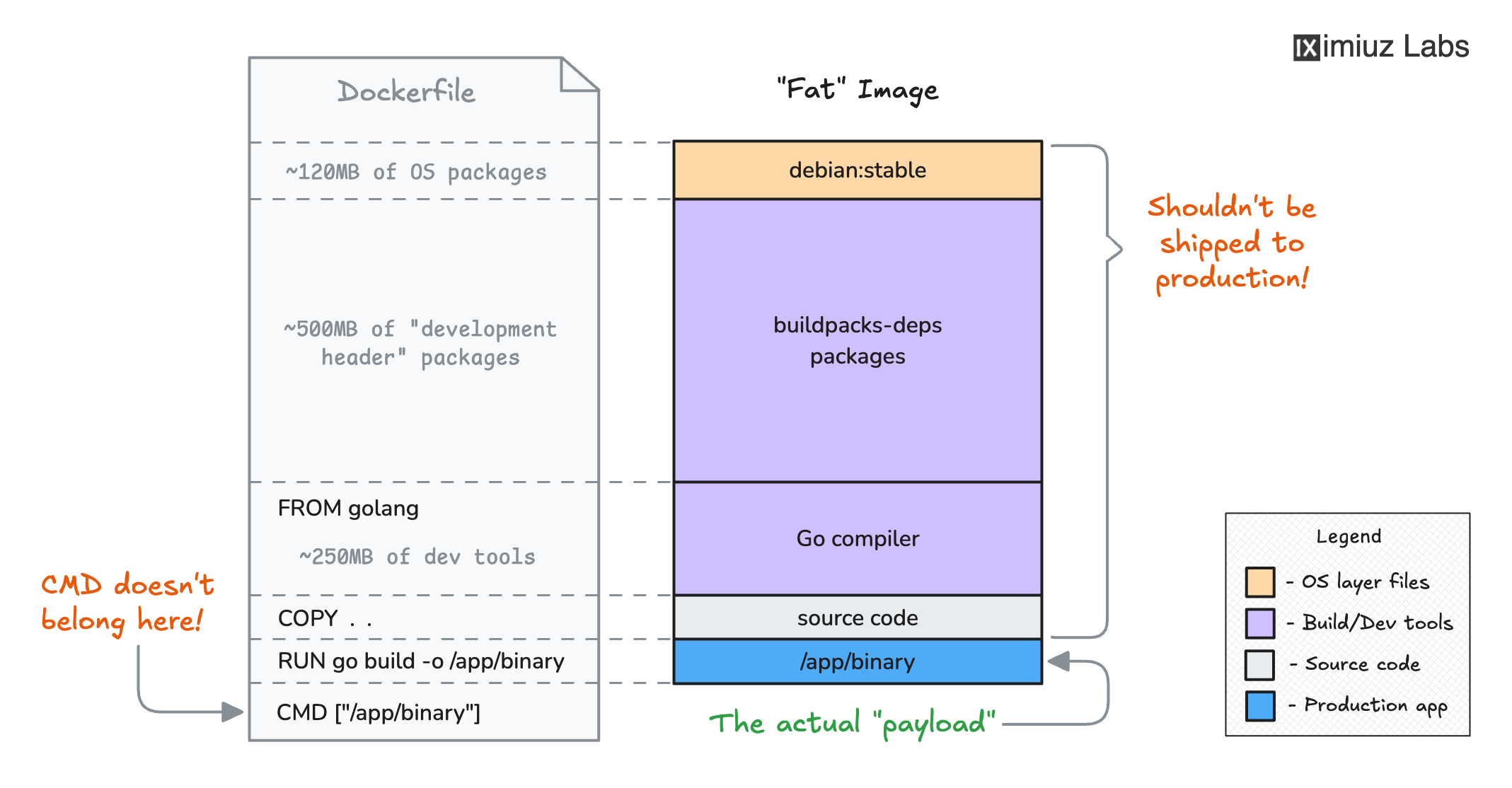

How NOT to structure a Dockerfile for a Go application.

The gotcha is that such an image would include not only the application itself (the part you want in production) but also the entire Go compiler toolchain and all its dependencies (the part you most certainly don't want in production):

trivy image -q golang:1.23

golang:1.23 (debian 12.7)

Total: 799 (UNKNOWN: 0, LOW: 240, MEDIUM: 459, HIGH: 98, CRITICAL: 2)

The golang:1.23 brings more than 800MB of packages and about the same number of CVEs 🤯

How NOT to organize a Node.js application's Dockerfile

A similar but slightly more subtle example:

# DO NOT DO THIS IN YOUR DOCKERFILE

FROM node:22-slim

WORKDIR /app

COPY . .

RUN npm ci

RUN npm run build

ENV NODE_ENV=production

EXPOSE 3000

CMD ["node", "/app/.output/index.mjs"]

Unlike the golang image, the

node:22-slim is a valid choice for a production workload base image.

However, there is still a potential problem with this Dockerfile.

If you build an image using it,

you may end up with the following composition:

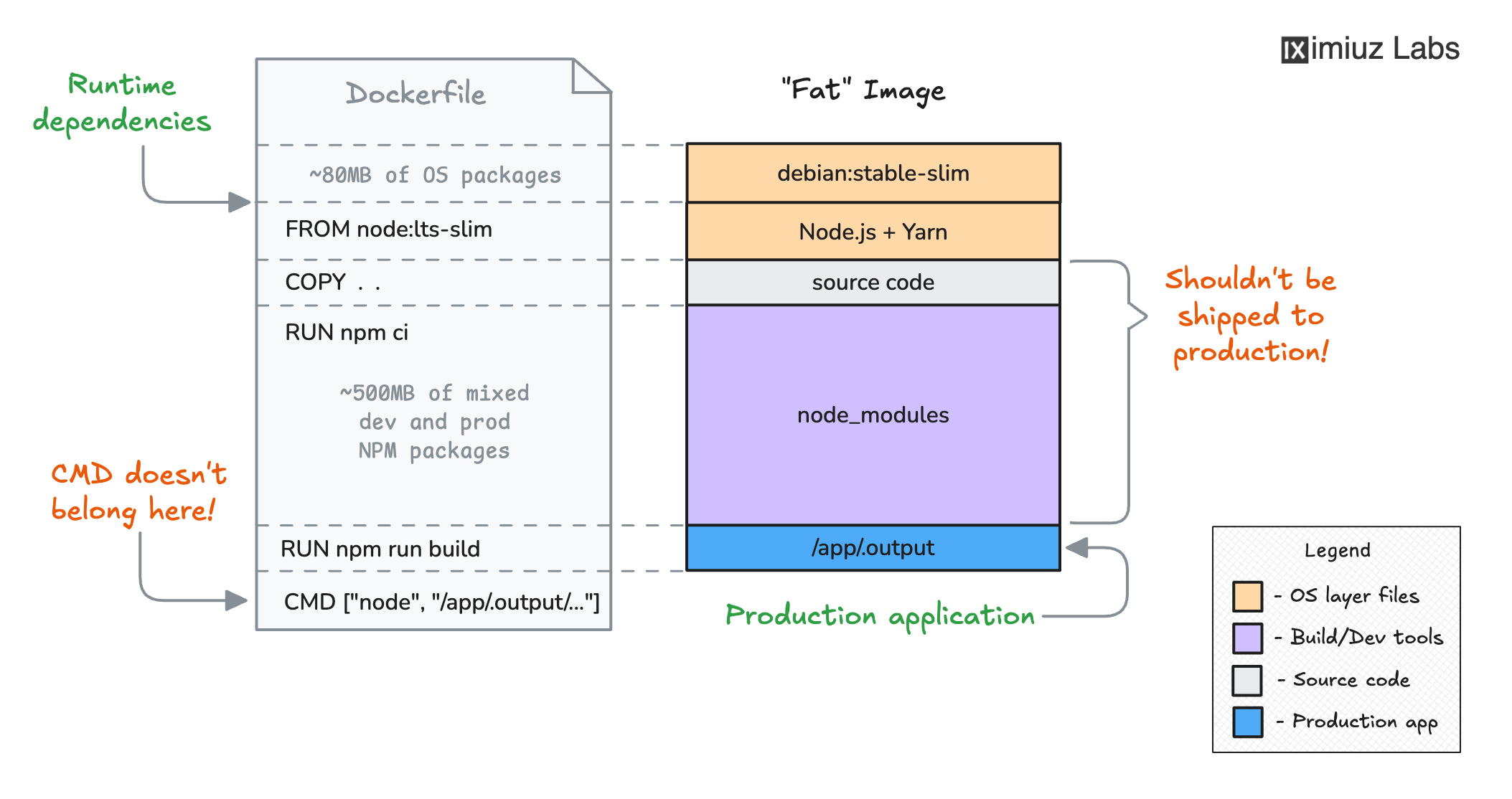

How NOT to structure a Dockerfile for a Node.js application.

The diagram shows the actual numbers for the iximiuz Labs frontend app, which is written in Nuxt 3.

If it used a single-stage Dockerfile like the above, the resulting image would have almost 500MB of node_modules,

while only about 50MB of the "bundled" JavaScript (and static assets) in the .output folder would constitute the (self-sufficient) production app.

This time, the "bloat" is caused by the npm ci step, which installs both production and development dependencies.

But the problem cannot be fixed by simply using npm ci --omit=dev because it'd break the consequent npm run build command

that needs both the production and the development dependencies to produce the final application bundle.

So, a more subtle solution is required.

Premium Materials

Official Content Pack required

This platform is funded entirely by the community. Please consider supporting iximiuz Labs by upgrading your membership to unlock access to this and all other learning materials in the Official Collection.

Support Development