Building an eBPF/XDP NAT-Based Layer 4 Load Balancer from Scratch

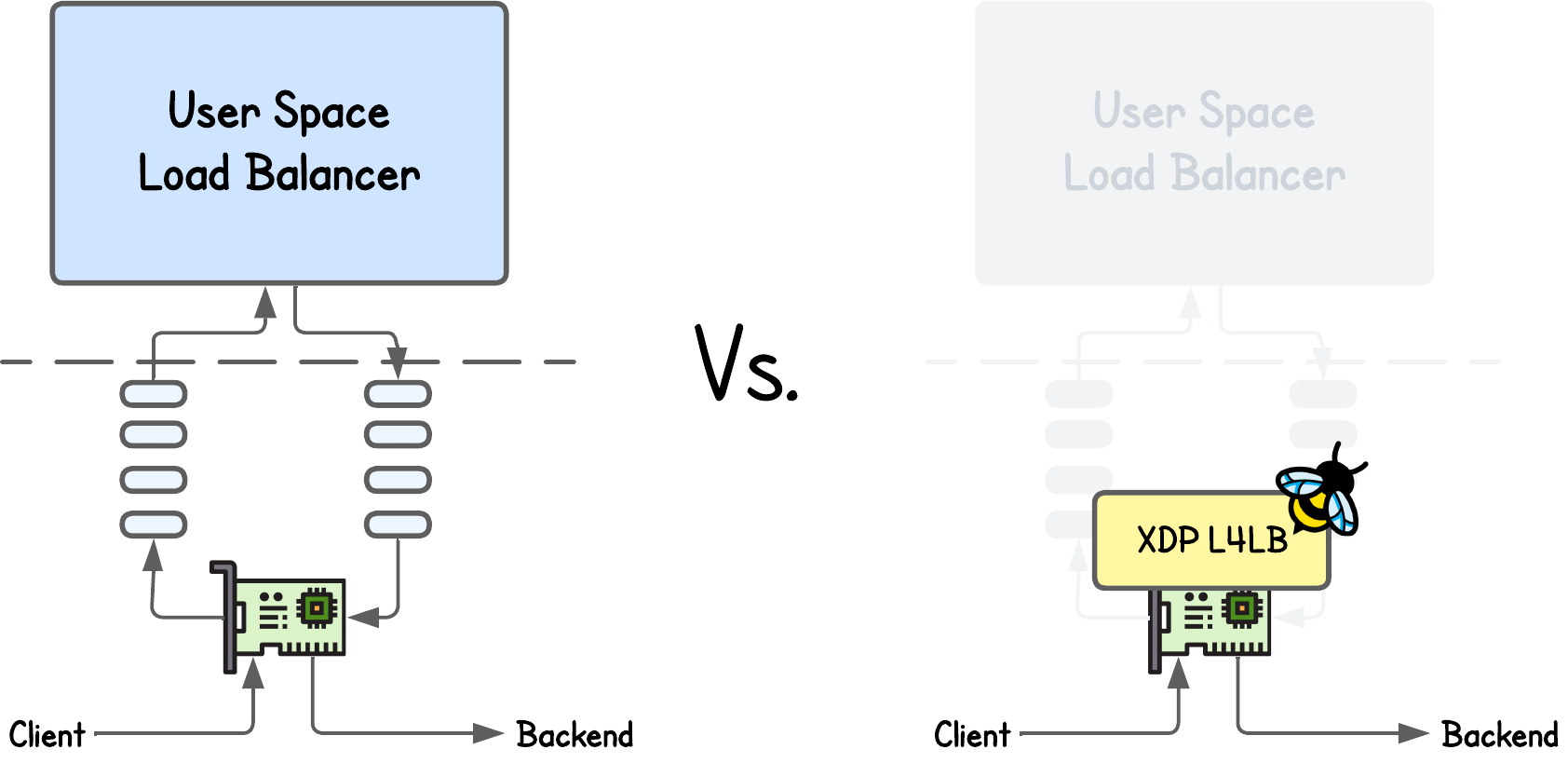

Traditional load balancers like NGINX and HAProxy typically operate in user space. Even when used purely for Layer 4 forwarding, every incoming packet must traverse the kernel’s networking stack to reach the user-space socket and then travel back down to the kernel before being forwarded to a backend.

Each of these traversals — crossing the user–kernel boundary, context switching, and buffer copying — adds microseconds of latency. It may sound small, but at millions of packets per second, this overhead quickly becomes a performance bottleneck that even modern hardware struggles to overcome.

To address this, eBPF/XDP-based Layer 4 load balancers were introduced — a concept that companies like Meta (Katran) and Cisco/Isovalent (Cilium) have already turned into production-grade systems.

💡 I’m referring specifically to Layer 4, since while eBPF-based Layer 7 load balancing is possible, so far I haven't seen any mature production solution yet—likely because implementing L7 features is too complex, outweighing the potential performance gains.

But how do these eBPF-based load balancers actually work?

Understanding how these projects leverage eBPF is quite hard — especially because there are no minimal, easy-to-run examples that clearly demonstrate the fundamentals.

This tutorial aims to fill that gap. We’ll walk through a simple XDP NAT Load Balancer implementation in roughly 200 lines of code (plus some boilerplate). And then in the upcoming tutorial, we’ll build on this foundation with features like DSR (Direct Server Return) Layer 2 load balancing and IPIP encapsulation.

NAT (Network Address Translation) and eBPF

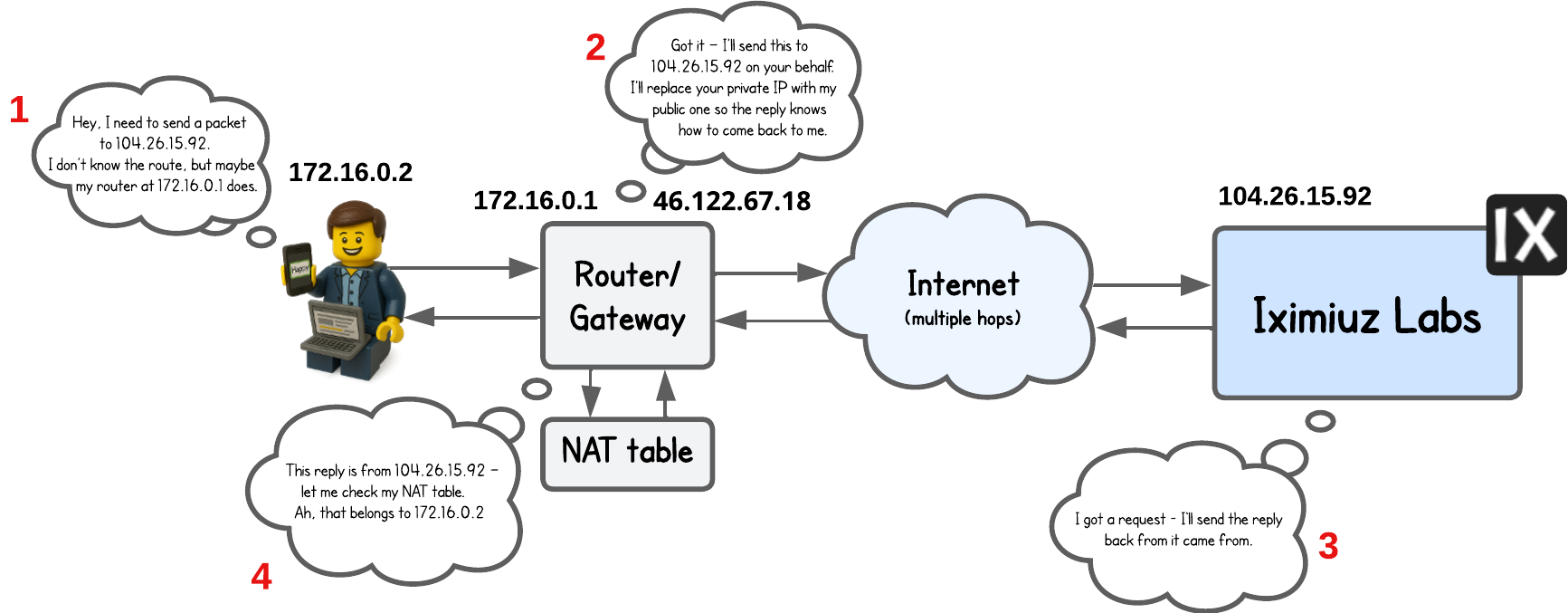

Before even putting load balancing into context, it’s important to first understand NAT (Network Address Translation) and how it would fit into the eBPF implementation.

In short, NAT is a mechanism that modifies/replaces IP address (and often port as well) in the packet header as it passes through the (routing) node that runs it.

We typically see it used on routers or gateways that connect two different networks (for example, a private LAN and the public internet), and on load balancers that rewrite packet destinations when forwarding traffic to backend servers.

Regardless of the use case, if you are new to this topic think of it like this (intentionally simplified):

Without going into too much details, NAT relies on a NAT table to define these translation rules and uses:

- Source Network Address Translation (SNAT) (outbound request) to replace the source IP address, and

- Destination Network Address Translation (DNAT) (incoming response) to replace the destination IP address.

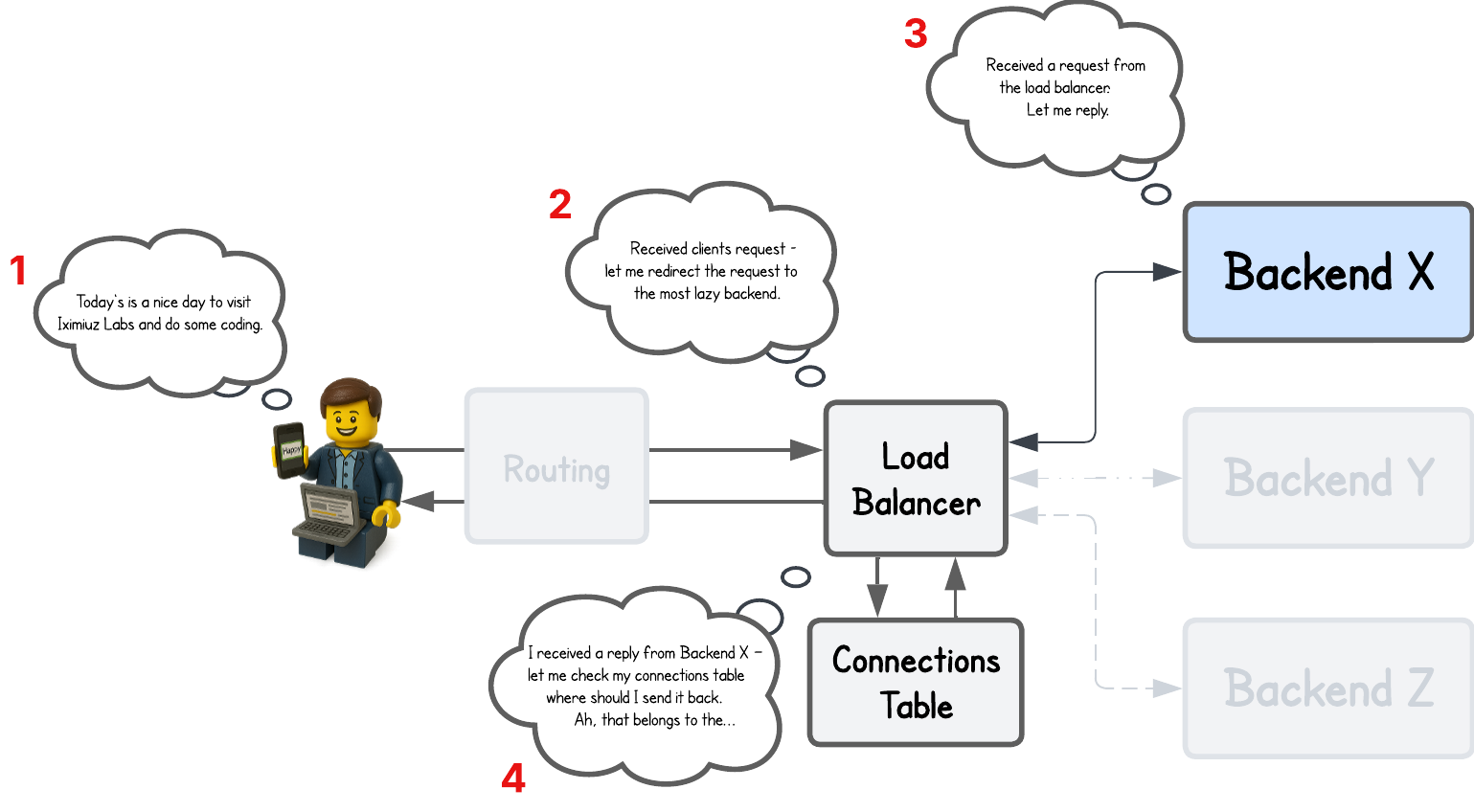

And this is similar to what a NAT-based Load Balancer (LB) also does (intentionally simplified):

It’s actually a bit trickier than that when you put virtual IPs (VIPs) and Direct Server Return (DSR) into the context, but we’ll get to that.

And while a load balancer doesn’t necessarily store this information in a NAT table like a router or gateway, it instead keeps it in some local variable or table — but the concept remains the same → it must remember which client made the request so it can send the backend’s response back to that same client.

Depending on the setup, the load balancer typically retains a 5-tuple client information — the client source IP, load balancer destination IP, client source port, load balancer destination port, and protocol (TCP/UDP).

This way, when the response comes back, the load balancer receives it from a connection defined by the backend’s source IP and port, the load balancer’s destination IP and port, and the specific protocol. Using this information, it knows exactly which client initiated the request.

Here’s an image that illustrates these mappings.

And when you think about this concept—storing client information on the request as it travels through the load balancer and retrieving it on the backend’s response—it’s relatively straightforward to implement in eBPF. We just need an eBPF map to hold this 5-tuple connection information.

...

// Lookup conntrack (connection tracking) information - actually eBPF map

// NO EXISTING CONNECTION: client request

// EXISTING CONNECTION: backend response

struct five_tuple_t in = {};

in.src_ip = ip->daddr; // LB destination IP

in.dst_ip = ip->saddr; // Client or Backend source IP

in.src_port = tcp->dest; // LB destination port same as source port from which it redirected the request to backend

in.dst_port = tcp->source; // Client or Backend source port

in.protocol = IPPROTO_TCP; // TCP protocol

struct endpoint *out = bpf_map_lookup_elem(&conntrack, &in);

if (!out) {

bpf_printk("Packet from client because no such connection exists yet");

...

// Store connection in the conntrack eBPF map so we can

// redirect backends response to the "correct" client

struct five_tuple_t in_loadbalancer = {};

in_loadbalancer.src_ip = ip->daddr; // LB IP

in_loadbalancer.dst_ip = backend->ip; // Backend IP

in_loadbalancer.src_port = tcp->source; // Client source port - equal to the LB source port since we don't modify it!

in_loadbalancer.dst_port = tcp->dest; // LB destination port

in_loadbalancer.protocol = IPPROTO_TCP; // TCP protocol

struct endpoint client;

client.ip = ip->saddr; // Store Client IP as value in the eBPF map

int ret = bpf_map_update_elem(&conntrack, &in_loadbalancer, &client, BPF_ANY);

...

} else {

bpf_printk("Packet from backend because the connection exists - "

"redirecting back to client");

...

}

...

Still confusing?

Whenever a client sends a request, our eBPF map (which acts like a simple NAT table) doesn’t yet contain any connection information. In that case, we create and store a new entry:

...

// Lookup conntrack (connection tracking) information - actually eBPF map

// NO EXISTING CONNECTION: client request

// EXISTING CONNECTION: backend response

struct five_tuple_t in = {};

in.src_ip = ip->daddr; // LB destination IP

in.dst_ip = ip->saddr; // Client or Backend source IP

in.src_port = tcp->dest; // LB destination port same as source port from which it redirected the request to backend

in.dst_port = tcp->source; // Client or Backend source port

in.protocol = IPPROTO_TCP; // TCP protocol

struct endpoint *out = bpf_map_lookup_elem(&conntrack, &in); // <- returns a NULL!

if (!out) {

bpf_printk("Packet from client because no such connection exists yet");

...

// Store connection in the conntrack eBPF map so we can

// redirect backends response to the "correct" client

struct five_tuple_t in_loadbalancer = {};

in_loadbalancer.src_ip = ip->daddr; // LB IP

in_loadbalancer.dst_ip = backend->ip; // Backend IP

in_loadbalancer.src_port = tcp->source; // Client source port - equal to the LB source port since we don't modify it!

in_loadbalancer.dst_port = tcp->dest; // LB destination port

in_loadbalancer.protocol = IPPROTO_TCP; // TCP protocol

struct endpoint client;

client.ip = ip->saddr; // Store Client IP as value in the eBPF map

int ret = bpf_map_update_elem(&conntrack, &in_loadbalancer, &client, BPF_ANY);

...

} else {

bpf_printk("Packet from backend because the connection exists - "

"redirecting back to client");

...

}

...

We’ll skip the low-level details of how the packet is actually rewritten and forwarded to the backend (we’ll cover that later). For now, assume the packet successfully reaches the backend, and the backend sends a response to the load balancer:

...

// Lookup conntrack (connection tracking) information - actually eBPF map

// NO EXISTING CONNECTION: client request

// EXISTING CONNECTION: backend response

struct five_tuple_t in = {};

in.src_ip = ip->daddr; // LB destination IP

in.dst_ip = ip->saddr; // Client or Backend source IP

in.src_port = tcp->dest; // LB destination port same as source port from which it redirected the request to backend

in.dst_port = tcp->source; // Client or Backend source port

in.protocol = IPPROTO_TCP; // TCP protocol

struct endpoint *out = bpf_map_lookup_elem(&conntrack, &in); // <- returns the client endpoint because the connection exist!

if (!out) {

bpf_printk("Packet from client because no such connection exists yet");

...

// Store connection in the conntrack eBPF map so we can

// redirect backends response to the "correct" client

struct five_tuple_t in_loadbalancer = {};

in_loadbalancer.src_ip = ip->daddr; // LB IP

in_loadbalancer.dst_ip = backend->ip; // Backend IP

in_loadbalancer.src_port = tcp->source; // Client source port - equal to the LB source port since we don't modify it!

in_loadbalancer.dst_port = tcp->dest; // LB destination port

in_loadbalancer.protocol = IPPROTO_TCP; // TCP protocol

struct endpoint client;

client.ip = ip->saddr; // Store Client IP as value in the eBPF map

int ret = bpf_map_update_elem(&conntrack, &in_loadbalancer, &client, BPF_ANY);

...

} else {

bpf_printk("Packet from backend because the connection exists - "

"redirecting back to client");

...

}

...

We can now see the full flow — how the client’s initial request creates an entry in the eBPF map (our “NAT table”) and how the load balancer, on the backend’s response, retrieves that entry to identify the client that made the request.

⚠️ For simplicity, this load balancer implementation only takes TCP connections into account, although UDP could easily be added.

I’m also intentionally hiding some parts of the code (... symbol), since we’ll cover them later. Open the full code in terminal if you want to jump ahead.

There’s that, but this isn’t really load balancing, because we still haven’t mentioned how the load balancer decides which backend to redirect the traffic to — nonetheless, there could be many.

Load Balancing

When it comes to load balancing, there are many algorithms that suit different uses cases better or worse. Just to name a few:

- Round Robin – Distributes requests sequentially across all servers in order, cycling back to the first when it reaches the last.

- Weighted Round Robin – Assigns more requests to certain backend servers using predefined weights.

- Least Connections – Sends new requests to the server with the fewest active connections, balancing uneven workloads efficiently.

- Hashing – Maps requests to backend servers by hashing a 5-tuple ensuring client always communicates with the same backend (session affinity)

- and many others..

The simplest one is obviously round-robin, but I want to make this tutorial a bit more interesting and instead show you how to implement simple hashing, so we can see how session affinity can be achieved.

What is session affinity and why is it important?

Session affinity (also known as “sticky sessions”) ensures that all requests from the same client are consistently routed to the same backend server.

This is important when a backend stores session-specific data in memory, since switching between servers would cause the session state to be lost or require complex synchronization.

Typical examples include:

- Web applications that store user sessions or authentication data locally on the server.

- Shopping carts or payment flows where in-memory context must persist across multiple requests.

- Real-time applications like chat or gaming servers maintaining a persistent TCP session.

Without session affinity, these requests could be sent to different backends, breaking continuity or forcing costly session synchronization.

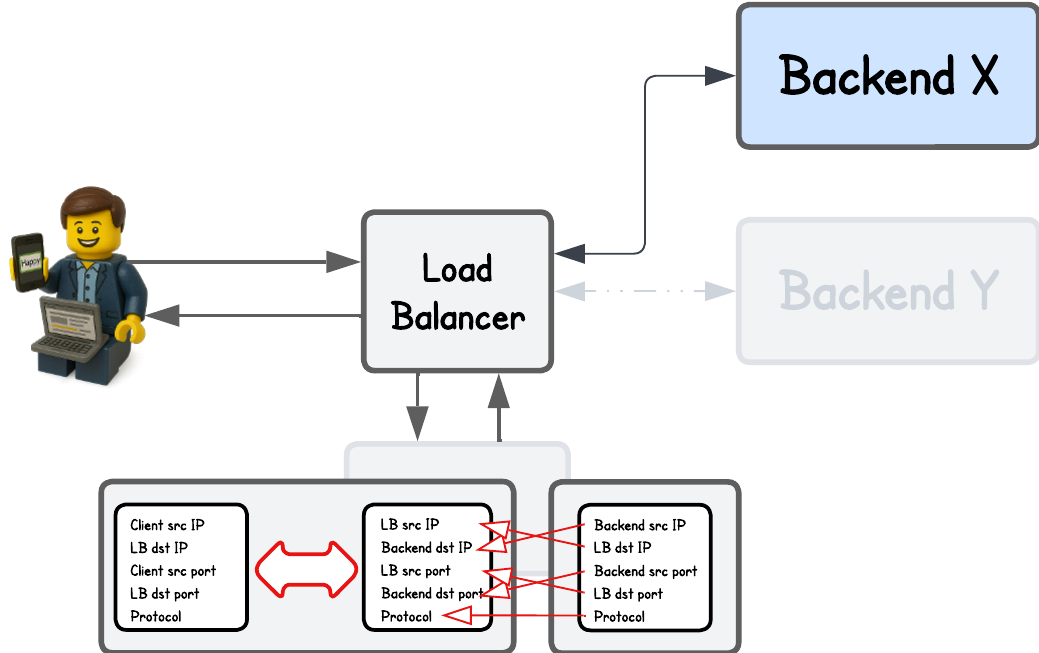

But now someone might ask — how on earth is hashing related to load balancing or routing in general?

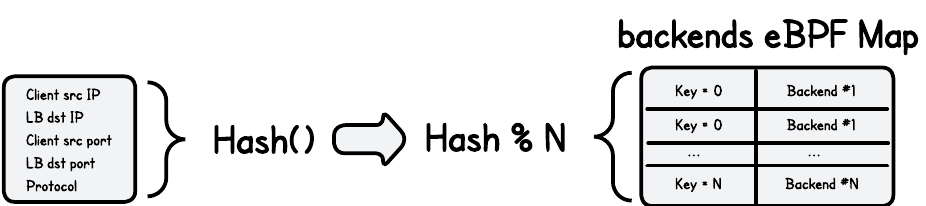

Here’s where it gets interesting: we already learned that every client connection to a load balancer has a unique 5-tuple — source IP, destination IP, source port, destination port, and protocol — meaning a hash of this 5-tuple will always give us a unique numeric value.

But not only that — it will always produce the same hash for the same 5-tuple.

By mapping that hash to a range of keys in an eBPF map containing backend endpoints, the load balancer can deterministically select a backend and route the traffic there (same hash → same backend).

Here's an image to illustrate this concept.

There are different hashing algorithms we can choose from like MurmurHash, Jenkins Hash, xxHash and FNV-1a (Fowler–Noll–Vo hash), which differ in speed, collision resistance, and how evenly they distribute values.

But this isn’t a math course, so I just implemented FNV-1a algorithm.

// FNV-1a hash implementation for load balancing

static __always_inline __u32 xdp_hash_tuple(struct five_tuple_t *tuple) {

__u32 hash = 2166136261U;

hash = (hash ^ tuple->src_ip) * 16777619U;

hash = (hash ^ tuple->dst_ip) * 16777619U;

hash = (hash ^ tuple->src_port) * 16777619U;

hash = (hash ^ tuple->dst_port) * 16777619U;

hash = (hash ^ tuple->protocol) * 16777619U;

return hash;

}

// Backends eBPF Map populated from user space

struct {

__uint(type, BPF_MAP_TYPE_ARRAY);

__uint(max_entries, NUM_BACKENDS);

__type(key, __u32);

__type(value, struct endpoint);

} backends SEC(".maps");

SEC("xdp")

int xdp_load_balancer(struct xdp_md *ctx) {

...

if (!out) {

bpf_printk("Packet from client because no such connection exists yet");

// Choose backend using simple hashing

struct five_tuple_t five_tuple = {};

five_tuple.src_ip = ip->saddr;

five_tuple.dst_ip = ip->daddr;

five_tuple.src_port = tcp->source;

five_tuple.dst_port = tcp->dest;

five_tuple.protocol = IPPROTO_TCP;

// Hash the 5-tuple for persistent backend routing and

// perform modulo with the number of backends (NUM_BACKENDS=2 hardcoded for simplicity)

__u32 key = xdp_hash_tuple(&five_tuple) % NUM_BACKENDS;

// Lookup calculated key and retrieve the backend endpoint information

struct endpoint *backend = bpf_map_lookup_elem(&backends, &key);

...

💡 Ideally, we’d continuously monitor backend node health and update the backends eBPF map accordingly, but for simplicity, we assume no nodes are added or removed to keep this demo code lean.

⚠️ For simplicity, we also don’t redirect client requests to specific backend ports. Instead, we assume that both the load balancer and the backends listen on the same port for incoming requests.

Now we see how both NAT and simple hashing fit neatly into the load-balancing logic — but we still need to rewrite the network packet’s IP header and MAC addresses.

This is necessary because after the client’s request passes through the load balancer, the packet’s original source and destination no longer match the actual source. Without rewriting these headers, the backend would see the load balancer as the destination and the client as the source, and drop the packet.

Rewriting IP and MAC Addresses

Updating the packet headers in load balancer logic ensures that each node along the path — client, load balancer, and backend — can correctly send and receive packets as if they were just talking to a peer node.

For this proof of concept, we could technically rewrite the MAC addresses quite easily — by hardcoding the load balancer’s MAC address directly in our eBPF program and storing the backend MAC address beside the IP in the backends eBPF map.

But why hardcode this information when it already exists in the kernel’s tables, such as the FIB (Forwarding Information Base) and ARP (or NDP for IPv6)?

ip route show # Displays the kernel routing table — where to send traffic to reach different destinations

ip neigh show # Displays the ARP table mapping IP addresses to MAC addresses

So ideally, we would somehow simply query the kernel tables from eBPF like:

“How do I reach this node?”

→ “Use this interface, MAC addresses, and IPs (or possibly this next hop).”

And indeed, we can do exactly that using the bpf_fib_lookup() helper function.

In our NAT load balancer implementation, bpf_fib_lookup() first queries the kernel’s routing table to determine where a packet should be forwarded, based on the device on which it was received and its source and destination IP addresses. If the lookup succeeds, the kernel then consults the neighbor tables (ARP for IPv4) to resolve the appropriate MAC addresses.

More information about `bpf_fib_lookup()` helper

If you look at the documentation for bpf_fib_lookup(), you’ll notice that you can provide different flags as input arguments that determine the behavior of this helper.

For example:

BPF_FIB_LOOKUP_OUTPUT— Treat the packet as if it’s leaving the interface, instead of arriving on it (the default). This matters when your routing selection depends oniif/oifIP rules.- Combination of

BPF_FIB_LOOKUP_TBIDandBPF_FIB_LOOKUP_DIRECT— Bypass IP rules and perform a direct lookup in a specified routing table. It’s faster but not ideal if routing should follow IP rules. BPF_FIB_LOOKUP_SKIP_NEIGH- Query only the kernel’s routing tables and skip the neighbor table lookup.

There are other special flags, but it's best to check the official documentation for the most up-to-date list and exact names.

static __always_inline int fib_lookup_v4_full(struct xdp_md *ctx,

struct bpf_fib_lookup *fib,

__u32 src, __u32 dst,

__u16 tot_len) {

// Zero and populate only what a full lookup needs

__builtin_memset(fib, 0, sizeof(*fib));

// Hardcode address family: AF_INET for IPv4

fib->family = AF_INET;

// Source IPv4 address used by the kernel for policy routing and source

// address–based decisions

fib->ipv4_src = src;

// Destination IPv4 address (in network byte order)

// The address we want to reach; used to find the correct egress route

fib->ipv4_dst = dst;

// Hardcoded Layer 4 protocol: TCP, UDP, ICMP

fib->l4_protocol = IPPROTO_TCP;

// Total length of the IPv4 packet (header + payload)

fib->tot_len = tot_len;

// Interface for the lookup

fib->ifindex = ctx->ingress_ifindex;

return bpf_fib_lookup(ctx, fib, sizeof(*fib), 0);

}

SEC("xdp")

int xdp_load_balancer(struct xdp_md *ctx) {

...

// Store Load Balancer IP for later

__u32 lb_ip = ip->daddr;

struct bpf_fib_lookup fib = {};

struct endpoint *out = bpf_map_lookup_elem(&conntrack, &in);

if (!out) {

bpf_printk("Packet from client because no such connection exists yet");

// Choose backend using simple hashing

struct five_tuple_t five_tuple = {};

five_tuple.src_ip = ip->saddr;

five_tuple.dst_ip = ip->daddr;

five_tuple.src_port = tcp->source;

five_tuple.dst_port = tcp->dest;

five_tuple.protocol = IPPROTO_TCP;

__u32 key = xdp_hash_tuple(&five_tuple) % NUM_BACKENDS;

struct endpoint *backend = bpf_map_lookup_elem(&backends, &key);

if (!backend) {

return XDP_ABORTED;

}

// Perform a FIB lookup

int rc = fib_lookup_v4_full(ctx, &fib, ip->daddr, backend->ip,

bpf_ntohs(ip->tot_len));

if (rc != BPF_FIB_LKUP_RET_SUCCESS) {

log_fib_error(rc);

return XDP_ABORTED;

}

// Store connection in the conntrack eBPF map

struct five_tuple_t in_loadbalancer = {};

in_loadbalancer.src_ip = ip->daddr;

in_loadbalancer.dst_ip = backend->ip;

in_loadbalancer.src_port = tcp->source;

in_loadbalancer.dst_port = tcp->dest;

in_loadbalancer.protocol = IPPROTO_TCP;

struct endpoint client;

client.ip = ip->saddr;

int ret = bpf_map_update_elem(&conntrack, &in_loadbalancer, &client, BPF_ANY);

if (ret != 0) {

bpf_printk("Failed to update conntrack eBPF map");

return XDP_ABORTED;

}

// Replace destination IP with backends' IP

ip->daddr = backend->ip;

// Replace destination MAC with backends' MAC

__builtin_memcpy(eth->h_dest, fib.dmac, ETH_ALEN);

} else {

bpf_printk("Packet from backend because the connection exists - "

"redirecting back to client");

// Perform a FIB lookup

int rc = fib_lookup_v4_full(ctx, &fib, ip->daddr, out->ip,

bpf_ntohs(ip->tot_len));

if (rc != BPF_FIB_LKUP_RET_SUCCESS) {

log_fib_error(rc);

return XDP_ABORTED;

}

// Replace destination IP with clients' IP

ip->daddr = out->ip;

// Replace destination MAC with clients' MAC

__builtin_memcpy(eth->h_dest, fib.dmac, ETH_ALEN);

}

// Replace source IP with load balancers' IP

ip->saddr = lb_ip;

// Replace source MAC with load balancers' MAC

__builtin_memcpy(eth->h_source, fib.smac, ETH_ALEN);

...

⚠️ The only assumption when using bpf_fib_lookup() is that the necessary routing information already exists in the kernel tables.

If you check the kernel’s routing table, you’ll see the route is indeed present (in the lb tab):

ip route show

default via 192.168.178.2 dev eth0 # If the destination IP address doesn't match the local subnet (or any other specific route), it gets sent here

192.168.178.0/24 dev eth0 proto kernel scope link src 192.168.178.10 # Routes any destination IP in 192.168.178.0/24 through the eth0 interface

However, that’s not necessarily true for the ARP table (or NDP for IPv6). If we inspect it (in the lb tab):

ip neigh show

192.168.178.1 dev eth0 lladdr 26:d7:2a:71:94:c4 REACHABLE

192.168.178.2 dev eth0 lladdr ce:4a:a3:20:23:a2 REACHABLE

you’ll notice that entries for our backend nodes (backend-1, backend-2 tab) are missing. But we can easily populate it using (in the lb tab):

sudo ping -c1 192.168.178.11

sudo ping -c1 192.168.178.12

Now you should see:

192.168.178.1 dev eth0 lladdr 26:d7:2a:71:94:c4 REACHABLE

192.168.178.2 dev eth0 lladdr ce:4a:a3:20:23:a2 REACHABLE

192.168.178.11 dev eth0 lladdr 32:da:f7:c0:34:04 REACHABLE

192.168.178.12 dev eth0 lladdr ba:ba:f6:ea:11:34 REACHABLE

In production setups, this isn’t really an issue, since the load balancer continuously performs health checks against the backends and keeps these tables updated.

Running the Load Balancer

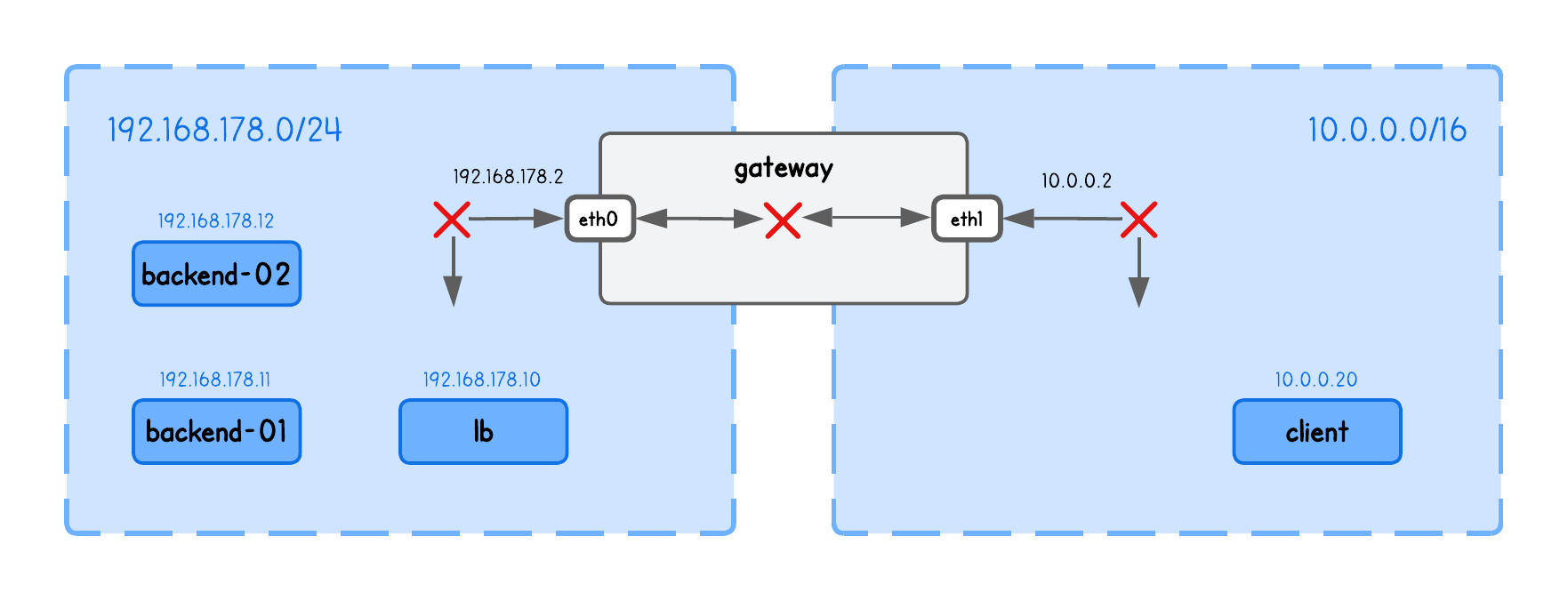

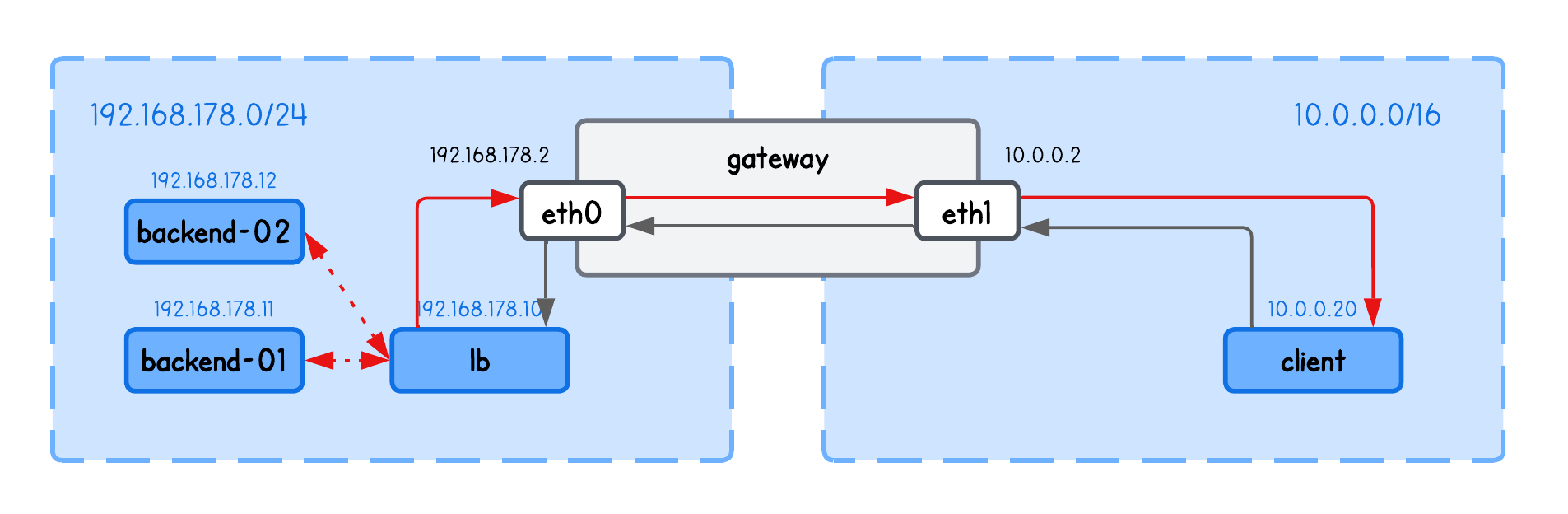

This playground has a network topology with five separate machines on two different networks:

lbin network192.168.178.10/24backend-01in network192.168.178.11/24backend-02in network192.168.178.12/24clientin network10.0.0.20/16gatewaybetween networks192.168.178.2/24and10.0.0.2/16

Before we can actually run our load balancer, we also need to enable packet forwarding between network interfaces (in the lb tab):

sudo sysctl -w net.ipv4.ip_forward=1

This allows the kernel to route packets it receives on one interface out through another — a requirement for the load balancer to forward client traffic to backend nodes.

⚠️ Make sure you've populated the ARP table with backends information using (in the lb tab):

sudo ping -c1 192.168.178.11

sudo ping -c1 192.168.178.12

See the previous section above for an explanation of why this is required.

Now build and run the XDP Load Balancer in the lb tab (inside the /lab directory), using:

go generate

go build

sudo ./lb -i eth0 -backends 192.168.178.11,192.168.178.12

What are these input parameters?

In short:

iexpects the network interface on which this XDP Load Balancer program will runbackendsThe list of backend IPs in this playground (you need to provide exactly two backends, due to the simplification described above for simple hashing)

Now run an HTTP server on every backend node in tabs backend-1, backend-2, using:

python3 -m http.server 8000

And query the Load Balancers node IP from the client tab, using:

curl http://192.168.178.10:8000

and confirm you see the requests indeed get routed through the load balancer node to one of the backends, by inspect eBPF load balancer logs (in the lb tab):

sudo bpftool prog trace

Congrats - you've came to the end of this tutorial 🎉

Before I let you go, some final remarks.

The nice thing about this setup is that it also works across different networks — the client, load balancer, and backend don’t need to be on the same subnet. This is possible because bpf_fib_lookup can retrieve the MAC address from a gateway or router when the backend resides on a different subnet.

Another benefit is that both the request and response pass through the load balancer, making it easier to apply custom network policies or perform additional inspection in both directions.

However, this approach isn’t always optimal.

Since the load balancer handles traffic in both directions, it consumes more resources and can become a bottleneck. Just think about it — the backend could simply respond directly to the client without routing the response back through the load balancer.

Another drawback is that the backend isn’t really aware of which client made the request. If you check the HTTP server logs, it appears as if the load balancer itself made the request (the IP at the beginning of the line).

192.168.178.10 - - [05/Jan/2026 02:06:07] "GET / HTTP/1.1" 200 -

In the next tutorial, we’ll address these shortcomings using XDP Layer 4 DSR (Direct Server Return) load balancing.