All The Ways To Loop and Iterate in eBPF

Loops are a common concept in almost every programming language, but in eBPF they can be a bit more complicated.

Not to mention, there are 5+ different ways to loop — so which one should you use and how?

The primary motivation behind supporting loops in programming is simple — reduce the complexity of the programs, where you need to perform a certain operation multiple times.

In eBPF, there are many cases where iteration comes useful, for example:

- Iterating over network packet headers or nested protocol headers

- Iterating over some arguments

- Parsing strings or buffers in chunks

In this lab, you'll learn how loops are supported in eBPF and what are the limitations of each implementation.

Loop Unrolling

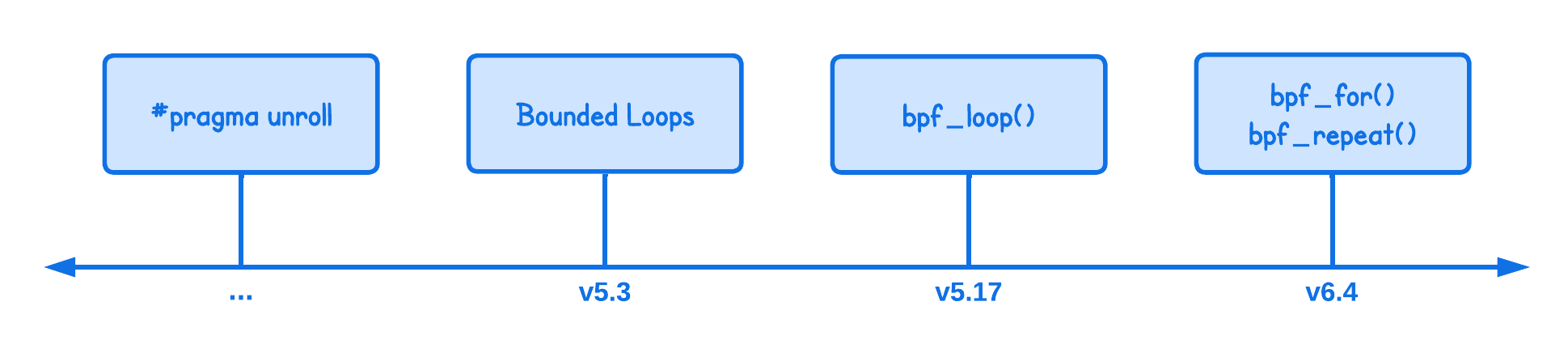

Before kernel version 5.3, eBPF programs could not (natively) loop, since this required a backward jump to an earlier instructions: execute some code then jump back and run it again.

At the time, this was considered unsafe since a backward jump could mean “run forever” and the eBPF verifier was not designed to handle that.

For a very long time, the workaround was to just unroll loops using #pragma unroll compiler directive:

int counter = 0;

#pragma clang loop unroll(full)

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_LOOPS; i++) {

counter++;

bpf_printk("Counting in loop_unroll...");

}

bpf_printk("Counted %dx times", counter);

The issue with this approach is that it’s not really a “native” looping mechanism.

Loops are unrolled during compile time into lines of instructions, which means that as iterations increase, the program binary grows accordingly.

int counter = 0;

#pragma clang loop unroll(full) (unrolled loop)

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_LOOPS; i++) { -----> counter++;

counter++; bpf_printk("Counting in loop_unroll...");

bpf_printk("Counting in loop_unroll..."); counter++;

} bpf_printk("Counting in loop_unroll...");

counter++;

bpf_printk("Counted %dx times", counter); NUM_LOOPS times...

This isn’t always a problem for simple use cases, but with more complex operations in the loop you can quickly hit the eBPF instruction limit which we’ll discuss in the next section.

Bounded Loops

From v5.3 onward, the eBPF verifier was able to follow branches backward as well as forward as part of its process of checking all the possible execution paths.

This enabled support for loops, referred to as the "bounded loops".

int counter = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_LOOPS; i++) {

counter++;

bpf_printk("Counting in bounded_loop...");

}

bpf_printk("Counted %dx times", counter);

Basically, same as before, just without the #pragma unroll directive.

And as mentioned before, in addition to handling loops, the eBPF verifier also needs to ensure that the program stays below the instruction limit.

💡 Until kernel version 5.4, the instruction limit was 4096 and then increased to 1M in later versions.

You can easily reach this limit with the simple example above by increasing the number of loops (NUM_LOOPS) to 1M, which will then produce the following error:

BPF program is too large. Processed 1000001 insn

And loops with more complex operations need even fewer iterations to exceed that limit.

Okay, but what is considered an instruction?

In eBPF, one instruction can be thought of as rough equivalent of a single operation or machine instruction. This can include:

- Loading or storing data (e.g., loading a value into a register).

- Arithmetic operations (e.g.,

counter++). - Comparisons (e.g.,

i < NUM_LOOPSin the loop condition).

But why is there even an instruction limit?

The eBPF program must release the CPU within a reasonable timeframe to allow the system to perform other tasks. But since there's no concept of time in the eBPF program, this limit is enforced by the number of instructions.

And if there would be no such limit, our eBPF program could significantly impact the system's performance, leading to issues such as disrupted networking and causing applications to lock up or run slowly.

For the sake of this, you can also print the number of instructions in your program inside the lab/main.go:

// NOTE: Change the eBPF program (objs.*.Info()) at your will

info, err := objs.LoopUnroll.Info()

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Failed to get eBPF Program info: %s", err)

}

insn, err := info.Instructions()

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Failed to get Instructions: %s", err)

}

log.Printf("Number of instructions in the eBPF Program: %d", len(insn))

While Loop

While not particularly much more interesting that the bounded loop, kernel version 5.3 also added support for while loops.

int counter = 0;

while (counter < NUM_LOOPS) {

counter++;

bpf_printk("Counting in while loop...");

}

bpf_printk("Counted %dx times", counter);

Now, onto a bit more eBPF native looping mechanisms.

bpf_loop() Helper Function

Sometimes, you really need to iterate over a "large range", which can be more complex than the 1M instruction limit imposed on bounded loops. To address this, kernel v5.17 introduced the bpf_loop helper function.

// Define the callback function for bpf_loop

static int increment_counter(void *ctx, int *counter) {

(*counter)++;

bpf_printk("Counting in bpf_loop_callback...");

return 0;

}

SEC("xdp")

int xdp_prog_bpf_loop_callback(struct xdp_md *ctx) {

int counter = 0;

// Use bpf_loop with the callback function

bpf_loop(NUM_LOOPS, increment_counter, &counter, 0);

bpf_printk("Counted %dx times", counter);

return XDP_PASS;

}

The helper function requires the following inputs:

- First argument: The number of iterations (limited to ~8 million).

- Second argument: The callback function called for each iteration.

- Third argument optional: A context variable that allows passing data from the main program to the callback function.

- Fourth argument optional: A "flags" parameter, which is currently unused but included for potential future use cases.

This helper allows for up to ~8 million iterations and is not constrained by the eBPF instruction limit because the loop occurs within the helper function, with the kernel managing it.

Or I should say, the verifier only needs to check the instructions of the callback function triggered once, as the helper function also ensures that the loop will always terminate without requiring the verifier to check each iteration.

You can verify this by printing the number of instructions as described above.

Open Coded Iterators

For similar reasons as to why the bpf_loop helper function was introduced, in v6.4, open-coded iterators were added.

Their primary intention is to provide a framework for implementing all kinds of iterators (e.g., cgroups, tasks, files). One of them is the numeric iterator that allows one to iterate over a range of numbers, enabling us to create a for loop.

Every iterator type has:

bpf_iter_<type>_newfunction to initialize the iteratorbpf_iter_<type>_nextfunction to get the next element, andbpf_iter_<type>_destroyfunction to clean up the iterator

For example, in the case of the numeric iterator, these are bpf_iter_num_new, bpf_iter_num_next and bpf_iter_num_destroy functions.

And based on these iterators, eBPF provides bpf_for helper function for a more natural feeling way to write the above:

int counter = 0;

bpf_for(counter, 0, NUM_LOOPS) {

counter++;

bpf_printk("Counting in bpf_for helper...");

}

bpf_printk("Counted %dx times", counter);

And also a bpf_repeat helper:

int counter = 0;

bpf_repeat(NUM_LOOPS) {

counter++;

bpf_printk("Counting in bpf_repeat_helper...");

}

bpf_printk("Counted %dx times", counter);

💡 I have explicitly added the definitions of bpf_for and bpf_repeat helper functions so you can see how they are build using the numeric iterators.

The advantage of this method is that the verifier is not required to check every iteration, as with a bounded loop, and it doesn't require a callback function like with the bpf_loop helper.

⚠️ While I haven't explicitly mentioned that above, for all of the looping mechanisms discussed so far, the number of iterations (NUM_LOOPS) must be known at compile time and remain constant for the lifetime of the program.

This is enforced by the verifier that needs to ensure the program finishes in an acceptable time.

Run the Code Examples

I’ve intentionally grouped all looping mechanisms into a single program to make it easier to navigate and to build a clear mental model of how each approach works.

Start by uncommenting the eBPF program you want to run in lab/main.go:

tp, err := link.Tracepoint(

"syscalls",

"sys_enter_execve",

//objs.LoopUnroll,

//objs.BoundedLoop,

//objs.WhileLoop,

objs.BpfForHelper,

//objs.BpfLoopCallback,

//objs.BpfRepeatHelper,

nil,

)

Only one loop implementation should be enabled at a time.

Now, build and execute the program from the lab directory using:

go generate

go build

sudo ./loop

Since this is an artificial example, the looping concepts are demonstrated using the tracepoint/syscalls/sys_enter_execve hook. In practice, the same looping patterns apply to any eBPF hook.

To confirm that the loop is executing, open another terminal and inspect the eBPF logs:

sudo bpftool prog trace

💡 If you don’t see any output right away, try running a few arbitrary Linux commands in another terminal tab—for example, ls or echo "hello eBPF". These will trigger our eBPF program and produce log output.

Congrats, you've came to the end of this tutorial. 🥳

Before I let you go, last little tip I want to share: since v5.13, you can use the bpf_for_each_map_elem helper to iterate over maps, so you don’t need to write explicit loops anymore.