Docker Containers vs. Kubernetes Pods - Taking a Deeper Look

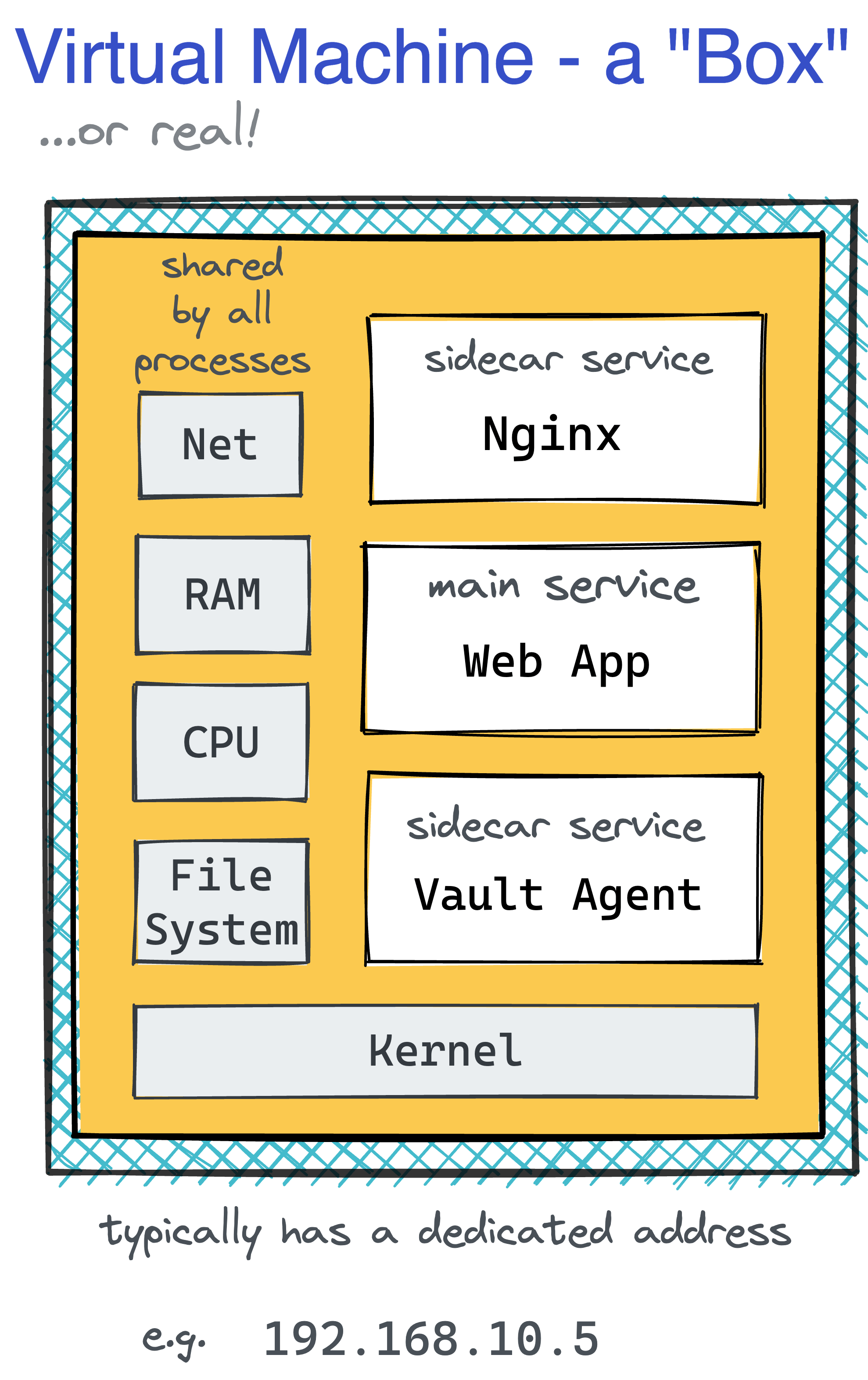

A container could have become a lightweight VM replacement.

However, the most widely used form of containers, popularized by Docker and later standardized by OCI,

encourages you to have just one process service per container.

Such an approach has a few significant upsides -

increased isolation, simplified horizontal scaling, higher reusability, etc.

However, this design also has a major drawback - in the real world, virtual machines rarely run just one service.

Thus, the container abstraction might often be too limited for a fully-featured VM replacement.

While Docker were trying to offer workarounds to create multi-service containers, Kubernetes made a bolder step and chose as its smallest deployable unit not a single but a group of cohesive containers, called a Pod.

For engineers with prior VM or bare-metal experience, it should be relatively easy to grasp the idea of Pods, or so it may seem... 🙈

One of the first things you learn when beginning working with Kubernetes is that each Pod is assigned a unique IP address and a hostname. Furthermore, containers within a Pod can communicate with each other via localhost. Thus, it quickly becomes clear that a Pod resembles a server in miniature.

After a while, though, you realize that every container in a Pod gets an isolated filesystem and that from inside one container, you don't see files and processes of the other containers of the same Pod. So, maybe a Pod is not a tiny little server but just a group of containers with shared network devices?

But then you learn that containers in one Pod can communicate via shared memory and other typical Linux IPC means! So, probably the network namespace is not the only shared thing...

That last finding was the final straw for me, and I decided to deep dive and see with my own eyes:

- How Pods are implemented under the hood;

- What the actual difference between a Pod and a Container is;

- What it would take to create a Pod using standard Docker commands.

Sounds interesting? Then join me on the journey! At the very least, it may help you solidify your Linux, Docker, and Kubernetes skills.

The OCI Runtime Spec doesn't limit container implementations to only Linux containers, i.e., the ones implemented with namespaces and cgroups. However, unless otherwise is stated explicitly, the word container in this article refers to this rather traditional form.

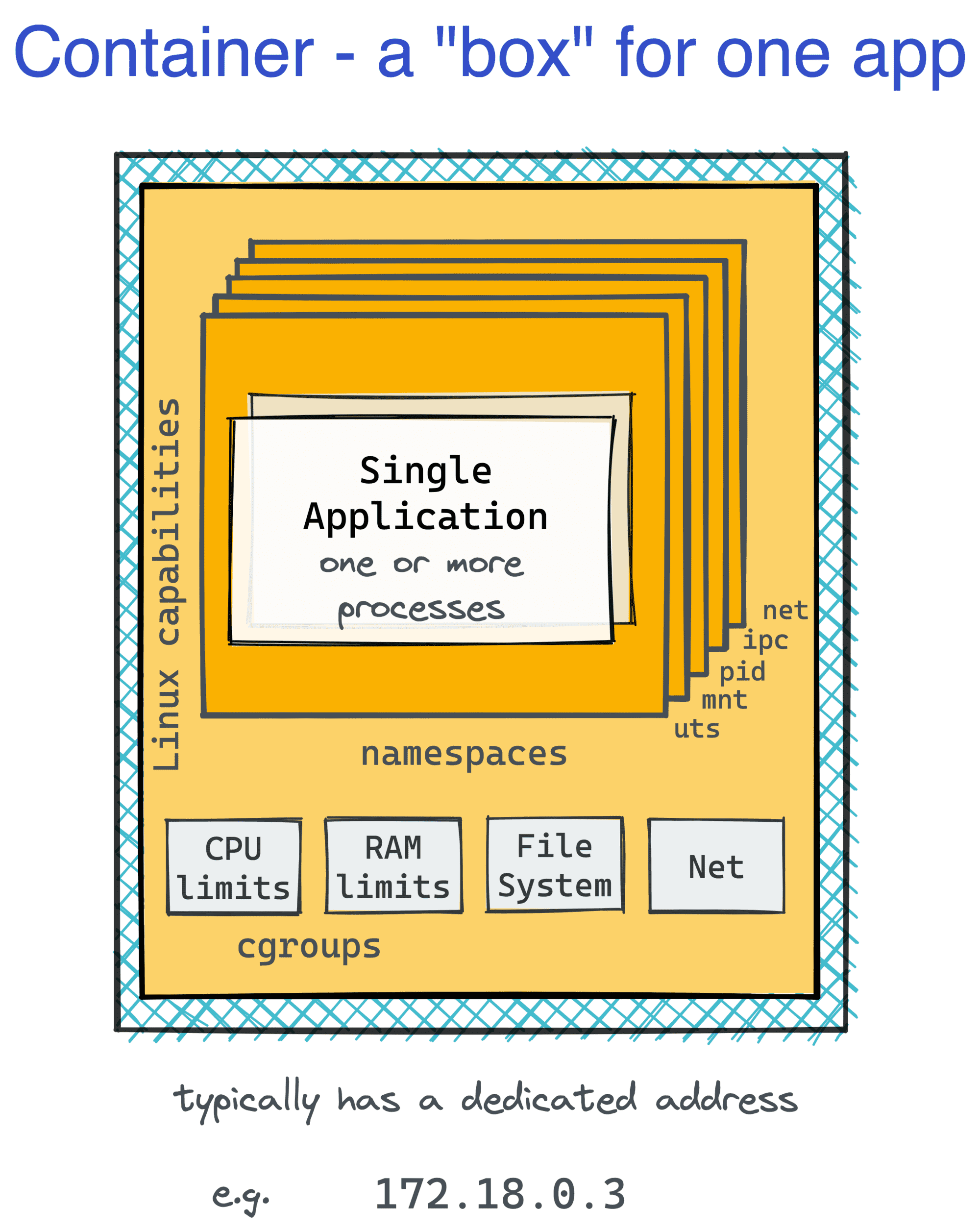

Examining a container

Let's start our guinea-pig container:

docker run --name foo --rm -d --memory='512MB' --cpus='0.5' nginx:alpine

Inspecting container's namespaces

Firstly, it'd be interesting to see what isolation primitives were created when the container started.

Here is how you can find the container's namespaces:

NGINX_PID=$(pgrep --oldest nginx)

sudo lsns -p ${NGINX_PID}

NS TYPE NPROCS PID USER COMMAND

...

4026532253 mnt 3 1269 root nginx: master process nginx -g daemon off;

4026532254 uts 3 1269 root nginx: master process nginx -g daemon off;

4026532255 ipc 3 1269 root nginx: master process nginx -g daemon off;

4026532256 pid 3 1269 root nginx: master process nginx -g daemon off;

4026532258 net 3 1269 root nginx: master process nginx -g daemon off;

4026532319 cgroup 3 1269 root nginx: master process nginx -g daemon off;

The namespaces used to isolate our nginx container are:

- mnt (Mount) - the container has an isolated mount table.

- uts (UNIX Time-Sharing) - the container is able to have its own hostname and domain name.

- ipc (Interprocess Communication) - processes inside the container can communicate via system-level IPC only to processes inside the same container.

- pid (Process ID) - processes inside the container are only able to see other processes inside the same container or inside the same pid namespace.

- net (Network) - the container gets its own set of network devices, IP protocol stacks, port numbers, etc.

- cgroup (Cgroup) - the container has its own virtualized view of the cgroup filesystem (not to be confused with cgroup mechanism itself).

Notice how the User namespace wasn't used! The OCI Runtime Spec mentions the user namespace support.

However, while Docker can use this namespace for its containers,

it doesn't do it by default due to the inherent limitations and extra operational complexity that it may add.

Thus, the root user in a container is likely the root user from your host system. Beware!

Level up your Server Side game — Join 25,000 engineers who receive insightful learning materials straight to their inbox

Another namespace on the list that requires a special callout is cgroup. It took me a while to understand that the cgroup namespace is not the same as the cgroups mechanism. Cgroup namespace just gives a container an isolated view of the cgroup pseudo-filesystem (which is discussed below).

Inspecting container's cgroups

Linux namespaces make processes inside a container think they run on a dedicated machine. However, not seeing any neighbors doesn't mean being fully protected from them. Some hungry neighbors can accidentally consume an unfair share of the host's resources.

Cgroups to the rescue!

The cgroup limits for a given process can be checked by examining its node in the cgroup pseudo-filesystem (cgroupfs) that is usually mounted at /sys/fs/cgroup.

But first, we need to figure out the path to the cgroupfs subtree for the process of interest:

sudo systemd-cgls --no-pager

Control group /:

-.slice

...

│

└─system.slice

...

│

├─docker-866191e4377b052886c3b85fc771d9825ebf2be06f84d0bea53bc39425f753b6.scope …

│ ├─1269 nginx: master process nginx -g daemon off;

│ └─1314 nginx: worker process

...

Then list the cgroupfs subtree:

ls -l /sys/fs/cgroup/system.slice/docker-$(docker ps --no-trunc -qf name=foo).scope/

...

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 27 11:12 cpu.max

-r--r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 27 11:12 cpu.stat

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 27 11:12 cpu.weight

...

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 27 11:51 io.max

-r--r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 27 11:12 io.stat

...

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 27 11:12 memory.high

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 27 11:12 memory.low

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 27 11:12 memory.max

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 27 11:12 memory.min

...

-r--r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 27 11:42 pids.current

-r--r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 27 11:51 pids.events

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Sep 27 11:12 pids.max

And to see the memory limit in particular, one needs to read the value in the memory.max file:

cat /sys/fs/cgroup/system.slice/docker-$(docker ps --no-trunc -qf name=foo).scope/memory.max

536870912 # Exactly 512MB that were requested at the container start.

Interesting that starting a container without explicitly setting any resource limits configures a cgroup slice for it anyway.

I haven't really checked, but my guess is that while CPU and RAM consumption is unrestricted by default,

cgroups might be used to limit some other resource consumption and device access (e.g., /dev/sda and /dev/mem) from inside a container.

Here is how the container can be visualized based on the above findings:

Premium Materials

Official Content Pack required

This platform is funded entirely by the community. Please consider supporting iximiuz Labs by upgrading your membership to unlock access to this and all other learning materials in the Official Collection.

Support Development