How Container Networking Works: Building a Bridge Network From Scratch

Working with containers can feel like magic at times. In a good way for those who understand the internals and in a terrifying - for those who don't. Luckily, we've been looking under the hood of the containerization technology for quite some time already and even managed to uncover that containers are just isolated and restricted Linux processes, that images aren't really needed to run containers, and that, on the contrary, to build an image we may need to run containers.

Now comes a time to tackle the container networking problem. Or, more precisely, a single-host container networking problem. In this article, we are going to answer the following questions:

- How to virtualize network resources to make containers think they have individual network environments?

- How to turn containers into friendly neighbors and teach to communicate with each other?

- How to reach the outside world (e.g. the Internet) from the inside of a container?

- How to reach containers running on a Linux host from the outside world?

- How to implement Docker-like port publishing?

While answering these questions, we'll set up a single-host container network from scratch using standard Linux tools. As a result, it'll become apparent that the magic of container networking emerges from a combination of much more basic Linux facilities:

- Network namespaces (netns)

- Virtual Ethernet devices (veth)

- Virtual network switches (bridge)

- IP routing and network address translation (NAT).

Let's get started! 🚀

Level up your Server Side game — Join 20,000 engineers who receive insightful learning materials straight to their inbox

Prerequisites

Basic bash scripting and Linux command line knowledge are assumed, but no coding skills are required. Examples in this tutorial were tested on Ubuntu 22.04, and they will likely work on other modern Linux distros, too. It's a good idea to use an isolated and disposable sandbox environment to follow the tutorial, like the one provided on the right 👉

⚠️ BEWARE: Running the below commands directly on your computer's host OS may be harmful.

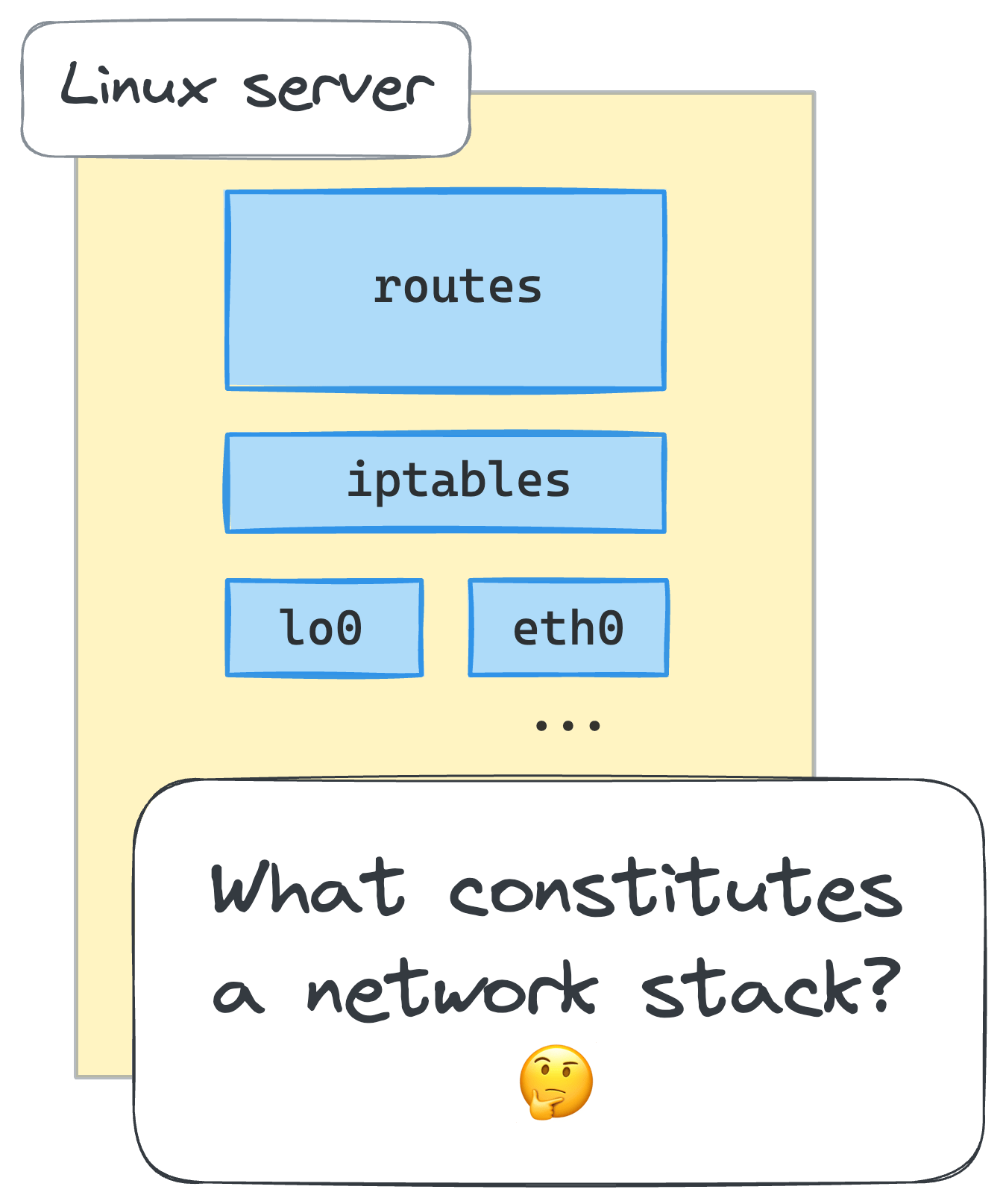

Main network environment components (devices, routing tables, firewall rules)

What constitutes a Linux network environment, a.k.a. a networking context? Well, obviously, a set of network devices. What else? Probably, some routing rules. And, of course not to forget - netfilter hooks, including those that are defined by iptables rules. There are more components, but the above should suffice for our purposes in this tutorial.

We can quickly forge a (no comprehensive) script to inspect the network environment:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

echo "# Network devices"

ip link list

echo -e "\n# Route table"

ip route list

echo -e "\n# iptables rules"

iptables --list-rules

Before running it, though, let's add a new iptables chain to make the set of rules more recognizable:

💡 All commands in this tutorial are supposed to be run as root or prefixed with sudo.

iptables --new-chain MY_CUSTOM_CHAIN

After that, execution of the inspect script on my machine produces the following output: If we run the script on a typical Linux machine, we'll get the output similar to the following:

~/inspect-net-context.sh

# Network devices

1: lo: <LOOPBACK,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 65536 qdisc noqueue state UNKNOWN mode DEFAULT group default qlen 1000

link/loopback 00:00:00:00:00:00 brd 00:00:00:00:00:00

...

4: eth0: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc pfifo_fast state UP mode DEFAULT group default qlen 1000

link/ether 92:b2:3d:42:ed:22 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

# Route table

default via 172.16.0.1 dev eth0

172.16.0.0/16 dev eth0 proto kernel scope link src 172.16.0.2

# iptables rules

-P INPUT ACCEPT

-P FORWARD ACCEPT

-P OUTPUT ACCEPT

-N MY_CUSTOM_CHAIN

Why do we need to inspect the network environment? Because we're going to start creating containers soon, and we want to make sure that each of them will get its own networking context, fully isolated from the host's and other containers' environments. For that, we'll need to get used to listing the network devices, routing and iptables rules.

👨🎓 For the sake of simplicity, instead of creating full-blown containers that leverage all possible Linux namespaces, in this tutorial we'll restrict the scope of virtualization to networking context only. Thus, a container and a network namespace below will be used interchangeably.

Creating the first container using a network namespace (netns)

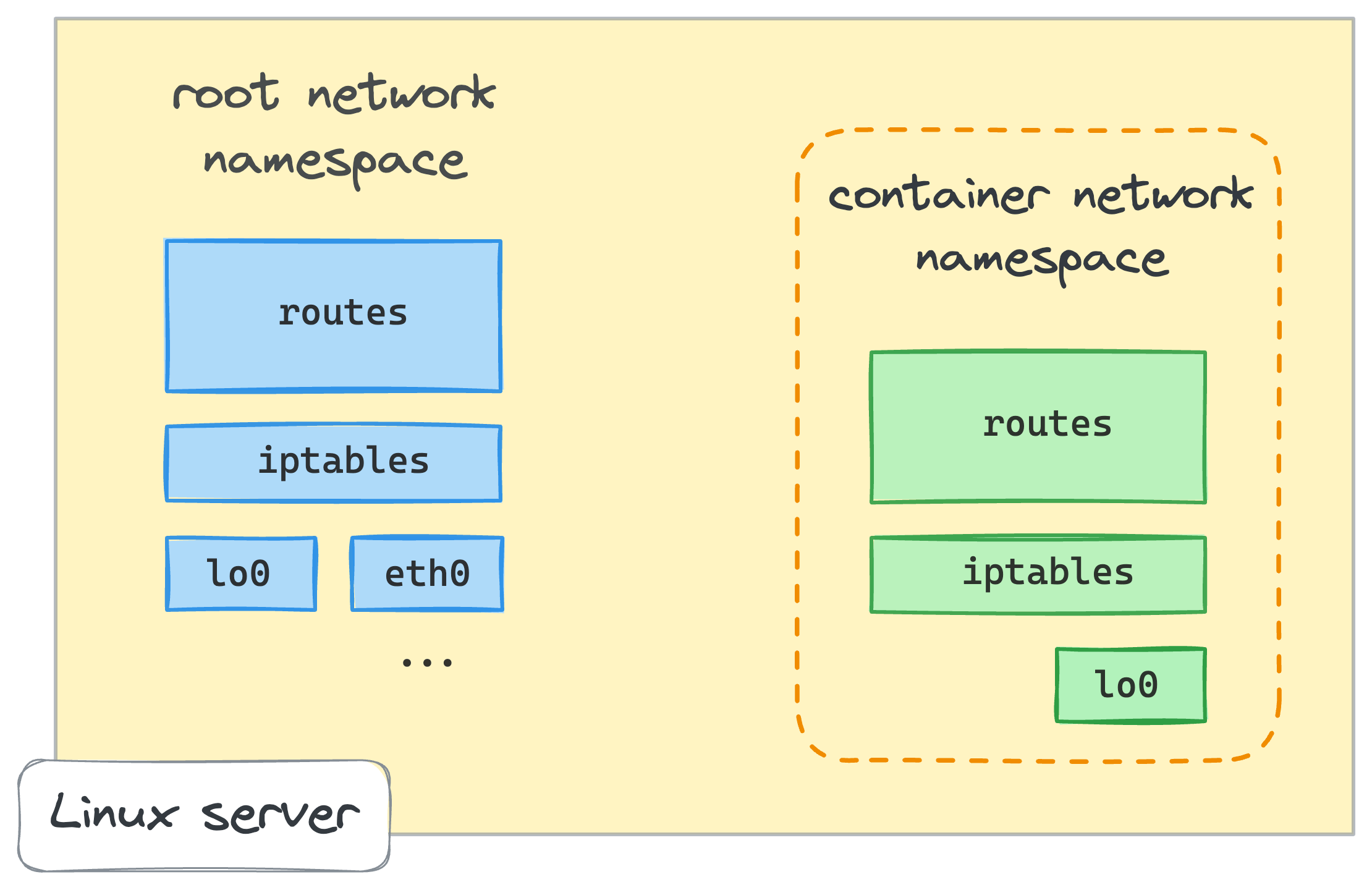

You've likely already heard, that one of the Linux namespaces used to create containers is called netns or network namespace.

From man ip-netns,

"network namespace is logically another copy of the network stack, with its own routes, firewall rules, and network devices."

One of the ways to create a network namespace in Linux is to use the ip netns add command

(where the ip utility comes from the de facto standard iproute2 collection):

ip netns add netns0

To check that the new namespace has been added to the system, run the following command:

ip netns list

netns0

How to start using the just created namespace?

There is another handy Linux utility called nsenter.

It enters one or more of the specified namespaces and then executes the given program in it.

For instance, here is how we can start a new shell session inside the netns0 namespace:

nsenter --net=/run/netns/netns0 bash

The newly created bash process now lives in the netns0 namespace.

If we run our inspect script in this new shell, we'll get the following output:

~/inspect-net-context.sh

# Network devices

1: lo: <LOOPBACK> mtu 65536 qdisc noop state DOWN mode DEFAULT group default qlen 1000

link/loopback 00:00:00:00:00:00 brd 00:00:00:00:00:00

# Route table

# Iptables rules

-P INPUT ACCEPT

-P FORWARD ACCEPT

-P OUTPUT ACCEPT

The above output clearly shows that the bash process that runs in the netns0 namespace has a totally different network environment -

there is no routing rules at all, no MY_CUSTOM_CHAIN iptables chain, and only one network device, the loopback. So far, so good!

🧙♂️ You shall not pass!

This tutorial is only available with the Official Premium Content Pack. Please consider upgrading your account to unlock all learning materials, get unlimited daily usage, and access to more powerful playgrounds. Help us keep this platform alive and growing!

Level up your Server Side game — Join 20,000 engineers who receive insightful learning materials straight to their inbox