Introduction

If you look at the Linux kernel’s networking stack code, it’s built to support a wide range of protocols and features — from IPv4/IPv6 and TCP/UDP to VLANs, tunnels such as VXLAN and GRE, as well as QoS and traffic shaping.

However, every processing step a packet goes through adds microseconds of latency. It may sound small, but at millions of packets per second, this overhead quickly becomes a performance bottleneck that even modern hardware struggles to overcome.

With this in mind, different kernel bypass techniques exist, such as DPDK or PF_RING ZC. These frameworks let user-space applications receive packets directly from the network hardware instead of going through the kernel.

But since these frameworks bypass the kernel, applications must often reimplement many of its networking features—which adds complexity as well as weakens the security mechanism normally provided by the kernel.

To address these shortcomings, XDP (eXpress Data Path) was introduced. It enables in-kernel packet processing that reuses existing kernel networking and security features instead of reimplementing them in user space.

That’s a rather rough comparison as DPDK can often be more performant, and XDP less complex to implement as it reuses many kernel features—but these are two technologies suited differently across environments, each with its own strengths and trade-offs.

To avoid making any enemies, in this skill path we’ll solely focus on:

- How XDP actually works?

- What kinds of applications is it best suited for?

- When should you consider using other eBPF program types higher up the stack?

This learning path will take you from parsing IPv4/IPv6, TCP/UDP, and ICMP traffic to more advanced use cases such as packet rate-limiting, firewalling and load balancing.

Happy 🐝-ing!

XDP Fundamentals: Setting the Stage

Loading tutorial...

In this first step, you’ll learn the fundamentals of eBPF and XDP through small example that parse packets across different network protocol layers and demonstrate how XDP actions work.

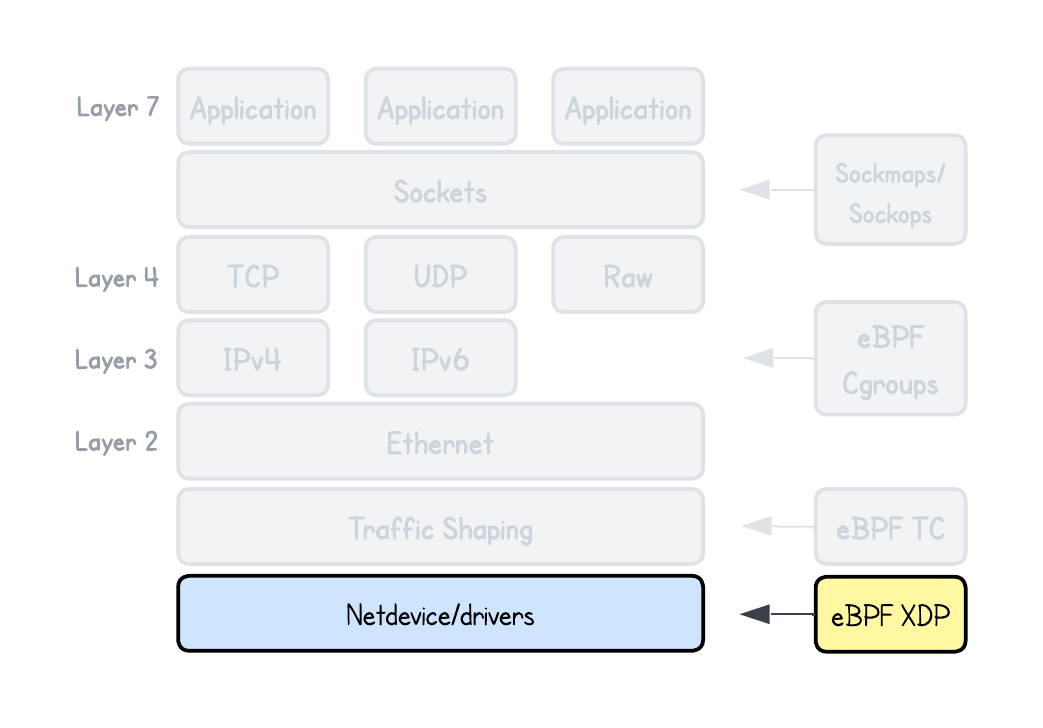

We also look at where eBPF/XDP programs attach in the networking stack, why different attachment points exist, and the key limitations of this program type.

Finally, you'll run your first XDP program and learn how these primitives come together to form the foundation of high-performance networking applications.

Network Traffic Rate Limiting with eBPF/XDP

Loading tutorial...

The complexity of different applications naturally depends on the problem, but one of the simplest—and also one of the first—examples I built early on was packet rate limiting.

Packet rate limiting is quite common today because of the large number of scrapers collecting data for AI training and the growing number of attacks that try to overwhelm servers or take down websites.

But it’s not only about limiting potentially bad traffic. Rate limiting also helps ensure fair API usage or enforce usage tiers (for example, 10 requests per second).

Building an eBPF-based Firewall with LPM Trie–Based IP Range Matching

Loading tutorial...

You have just learned how to rate-limit network traffic, so naturally, you might wonder how different an eBPF-based firewall really is from the rate limiter. After all, instead of rate-limiting packets, we could just block them entirely, right?

Well, not quite.

While our firewall implementation will only focus on filtering packets by client IP (not by ports, protocol, or fingerprinting), one ideally doesn’t want users to specify every single IP rule manually. In many cases, it would be much easier to allow one to whitelist or blacklist entire IP ranges instead.

Nonetheless, a simple IP-based firewall might work fine if you’re only whitelisting a few static addresses. But what if those IPs are dynamic and constantly changing within a certain range or subnet?

Building an eBPF/XDP NAT-Based Layer 4 Load Balancer from Scratch

Loading tutorial...

Traditional load balancers like NGINX and HAProxy typically operate in user space. Even when used purely for Layer 4 forwarding, every incoming packet must traverse the kernel’s networking stack to reach the user-space socket and then travel back down to the kernel before being forwarded to a backend.

Each of these traversals — crossing the user–kernel boundary, context switching, and buffer copying — adds microseconds of latency. It may sound small, but at millions of packets per second, this overhead quickly becomes a performance bottleneck that even modern hardware struggles to overcome.

To address this, eBPF/XDP-based Layer 4 load balancers were introduced — but how do these eBPF-based load balancers actually work?

Building an eBPF/XDP L2 Direct Server Return Load Balancer from Scratch

Loading tutorial...

One nice thing about the XDP NAT load balancer we just built is that both requests and responses flow through it which made the bidirectional network policy enforcement and packet inspection possible.

But this design actually has downsides. Handling traffic in both directions not only increases resource usage and can make the load balancer a bottleneck but also hides the original client identity, making per-user sessions and source-IP logging difficult.

To address these shortcomings, the Direct Server Return (DSR) model was introduced.

Building an eBPF/XDP IP-in-IP Direct Server Return Load Balancer from Scratch

Loading tutorial...

A key takeaway from the DSR L2 eBPF/XDP-based load balancer design was how the virtual IP can be shared between the load balancer and backend nodes, as well as keeping the IP header intact, allowing the backend to see the client’s IP.

While this worked nicely, L2 DSR relies on the fact that backend nodes need to be on the same L2 network as the load balancer.

This is quite a constraint, and not quite suitable for cloud environments, where nodes are often distributed across different virtual networks.

To overcome these limitations, DSR IP-in-IP load balancing was introduced.